Mongaup Homesteads

by Fred Fries

During this season of what appears to be

the winter that never was, it has become an ideal time to visit long

abandoned homesteads, searching for clues from the past that have been left

behind. The lack of the normal early winter blanket of snow has made easy

access in visiting old foundations and walls. Last October’s heavy snow

fall, which soon disappeared after that freak storm, has also been

beneficial in the search for lost artifacts among these ruins, matting down

the vegetative ground cover for easier walking and in some cases baring

historic treasures otherwise buried in vegetative debris.

During this season of what appears to be

the winter that never was, it has become an ideal time to visit long

abandoned homesteads, searching for clues from the past that have been left

behind. The lack of the normal early winter blanket of snow has made easy

access in visiting old foundations and walls. Last October’s heavy snow

fall, which soon disappeared after that freak storm, has also been

beneficial in the search for lost artifacts among these ruins, matting down

the vegetative ground cover for easier walking and in some cases baring

historic treasures otherwise buried in vegetative debris.

One interesting location which has numerous abandoned and forgotten homesteads is above DeBruce along the valley and watershed of the Mongaup Creek. The properties at this section of the Livingston Manor area has throughout its history remained as large parcels; ownership of these lots by Hardenbergh Patent descendants, land-rich landlords, tanners, lumber companies, Boy Scouts and lately, the State of New York. Being isolated from the bustling communities further down the valley, development in this section was meant mainly the clearing of virgin forests for a few subsistent hardscrabble farms and the workings from crews of lumbermen. With these early uses and now most of the area under the ownership by the State of New York, this section has been relatively untouched by the forces of modern progress, allowing remnants of earlier human passages and endeavors to survive.

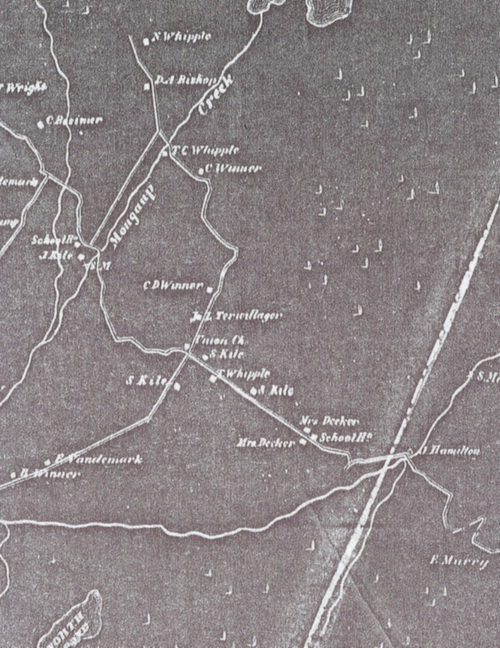

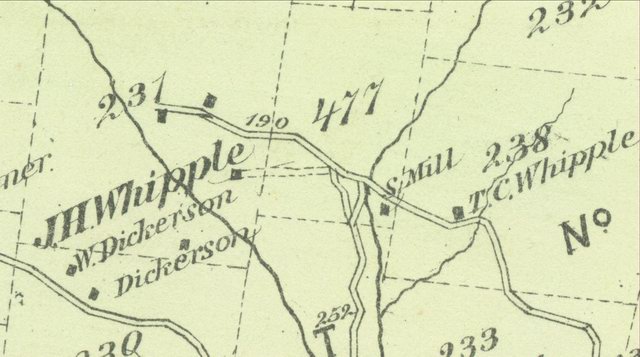

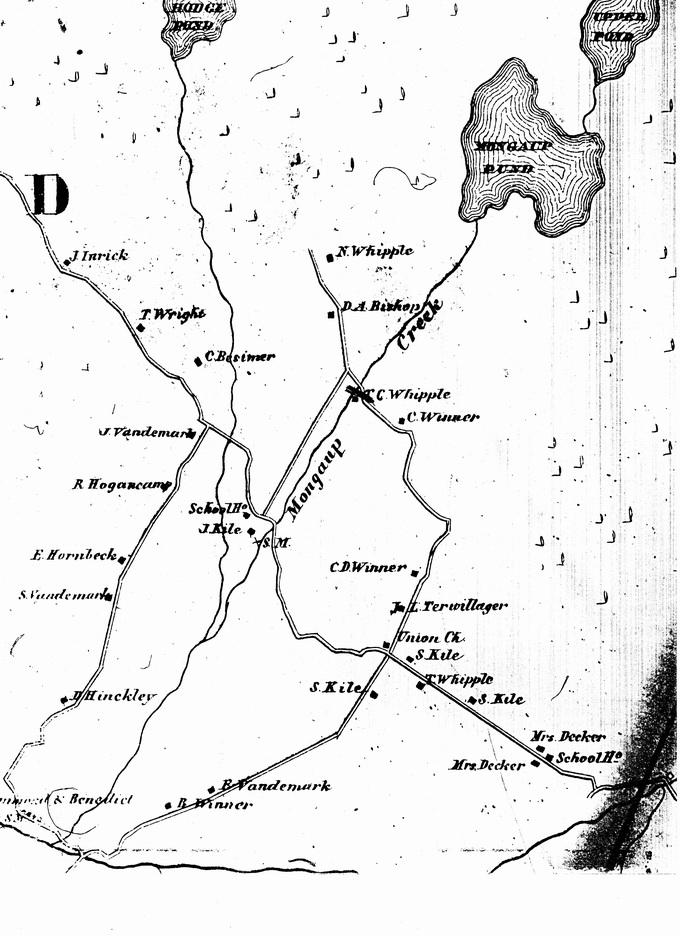

Included is a section of the Sullivan County Atlas, dated 1856, which shows this particular area of the Town of Rockland, along with the names of the families and their homestead’s locations. For those familiar with the area, Mongaup Pond would be the body of water on the upper edge of the map. The Mongaup Creek flows past the residence of Thomas C Whipple, which is the site of the falls on that creek. Further down the creek, near what was then the residence of Joseph Kile, would today be near the vicinity of the DEC fish hatchery. The road crossing there would be the Old Hunter Road, leading to Brown Settlement, which is noted on the map by the location of the “Union Ch.” Continuing along the Old Hunter Road, the river crossing at the homestead of “J Hamilton” would be today the settlement of Willowemoc.

Those who have hiked the Mongaup area trails leading to Frick or Hodge ponds most likely had parked their vehicle at the trailhead parking lot located on the end of the short spur road leading off from the Mongaup Pond Road. Though both the Frick Pond and Hodge Pond trails lead to historically interesting sites, the parking lot itself is within only a short distance from homestead ruins that, when examined, offer a glimpse into the family that settled there over 160 years ago.

David Bishop moved to the forests of

Mongaup from the lower Roundout valley section of Ulster County. With the

passage of the Delaware & Hudson Canal through that valley, much of the

local employment centered upon the canal; work on its construction, work

upon the barges, or the building of canal boats and other necessary

articles. Here, David Bishop learned the skill of fashioning oars out of

lumber, an occupation that would lead him to move his family,

Sarah,

his wife, two-year old Conrad and a newborn baby daughter, to the pristine

hardwood forests of Sullivan County in 1849. Out of the 100 acre forested

lot he claimed, David opened a small clearing of fourteen acres on an

elongated hillock, overlooking forested countryside strewn with glacier

deposited boulders. However, rocks and boulders still needed to be removed

from the opening cut out of the forest, which were dragged to the clearing’s

edge to form walls, or used as foundation walls for his house, barn and root

cellar.

Though the rocks were plentiful, the supply of good soil for cultivation purposes was less generous. By 1854, David had worked one acre of his farm into a suitable plot for planting. The choices of crops to plant were few, for the growing season short, except for one. Potatoes, perhaps the best crop to plant under less than ideal conditions, were planted, and in 1854, David’s potato crop yielded a harvest of seventy-five bushels. The remaining thirteen acres of cleared lands served as pasture lots for his three cows and their calves, along with two pigs.

The accompanying photograph show what appears to be the remains of the root cellar on the David Bishop homestead. Cut into the hillside, it sits about twenty feet away from the back of the remnants of the house foundation. Though the entrance and side walls have long collapsed, it appears to be of ample size for the storage of Bishop’s large harvest.

The Bishop family did not remain long in the Mongaup area, maybe staying less then ten years. As with most of their neighbors in this section, David and Sarah Bishop were not the owners of the land they worked and were required to pay some sort of rent to their landlord, John Hunter. Hunter married the daughter of Elias Debrosses, who had owned a vast tract of land in the Hardenbergh Patent, the aristocratic scheme of land ownership throughout the Catskills during the eighteenth century. Upon the death of her father, Hunter’s wife inherited the tract of land known as Great Lot Five, which includes the northern half of the Town of Rockland. During the 1840’s and 1850’s there had been dissatisfaction amongst the renters with their landlords in this section, leading to several confrontations. Bishop, however, was able to escape the shadow of his landlord and the agitation of fellow renters with the purchase his own land, a forty-one acre lot along the Sugar Loaf Brook outside of Grahamsville in the Town of Neversink. The 1860 census shows the Bishop family was then residing on the property he owned.

David Bishop may have been able to escape the landlord-renter confrontation during the period of the Anti-rent Wars, but he was unable to resist the call to arms during the national calamity of civil war. In August of 1862, the thirty-nine-year-old oar-maker, along with his sixteen-year-old son, Conrad Bishop, enlisted into the Mountain Regiment, the NY 156th, organized at Kingston, Ulster County. Throughout the year of 1863, the 156th served in the Union campaign throughout the swampy delta and bayou country along the Mississippi River in Louisiana. The tepid southern climate raised havoc with the northern soldiers, inflicting more casualties amongst the boys of the 156th than received from the enemy. David Bishop took ill that summer and died during August in a hospital at Baton Rouge. Young Conrad also became sick and was discharged with a physical disability. Military records state that he too died. The father is buried at Baton Rouge while the son’s whereabouts is unknown.

The remains

found upon the Bishop homestead show the locations of the house, barn and

probable root cellar. No discernable well location can be found, though a

cluster of stones not far from the ruins of the house may prove to be

covering up the well hole. Only two short segments of stone walls survive.

However, two other locations mark the edge of the clearing with a line of

stone, now buried under years of vegetative cover, that probably were

dragged from the opening but not yet made into wall. The shortness of the

Bishop family’s stay probably would not have been enough time to build

extensive walls. Fencing for his animals probably was either made up of

wooden rail or toggle cut from fallen trees. The unfinished stone walls and

the lack of pieces of barb wire fencing, more commonly used by the end of

the century, buried within older trees suggest that perhaps the Bishop

homestead was used for only a short period of time, if at all, after the

Bishop family moved away to the Town of Neversink.

The photograph shows the remains of the barn foundation. The root cellar can be seen in the distance behind the barn, dug into the hillside on the upper left of the image. The ruins of the house foundation, which would be in front of the root cellar, are not discernable in this photo.

The DEC’s Flynn Trail is a relatively easy two mile climb along the now-abandoned town road to Hodge Pond. However, immediately after leaving the trailhead parking lot, the trail sidesteps the old road and starts out as a foot path through the woods for a distance of two hundred yards, detouring around what was once the ranger’s cabin. Above the cabin, to the right of where the foot-trail re-enters upon the old roadbed, the hiker will notice the ruins of a fireplace along with its crumbling chimney. This would be the area of the Noah Whipple homestead, as shown upon the 1856 map.

The ruins found on this old homestead are not as easily identifiable as those found on the Bishop place a quarter of a mile away, the results due to the passage of time and some apparent alterations caused by the succession of ownership. In 1898, Patrick Flynn, a contractor and local railroad entrepreneur from Brooklyn, began the erection of a road, beginning on the Whipple farm, to reach Hodge Pond and erect his large mansion overlooking the pond.

Workers from his various projects in and

around New York City were brought up to his Sullivan County estate to work

on both projects. It is possible, and maybe probable, that the Whipple site

may have been used as housing for these workers, and maybe used by Flynn

himself until the completion of his more commodious structure at the pond.

Years later, after Flynn’s financial demise, numerous lumber concerns

operated over the vast woodland tract. The Whipple homestead, or the

buildings that remained, were probably used by the lumbermen as a lumber

camp. Reconstruction of the Flynn road by the town and other alterations

made within the vicinity further modify the site. However, the remains that

are left behind offer some insight not only to the early settlers, but also

for those who have followed.

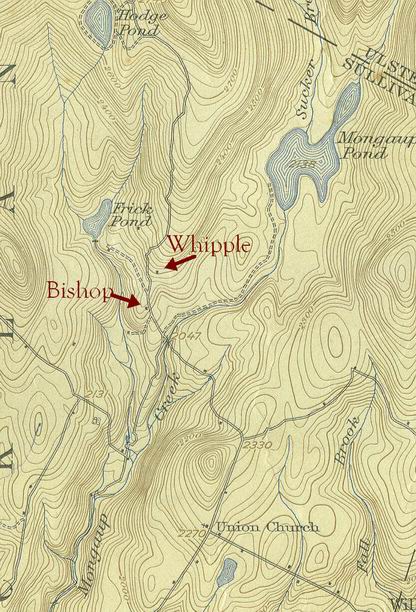

Included is the 1938 USGS map of the

Mongaup area, revised from the original data taken in 1911. Both the Whipple

and Bishop sites were still in existence at the time, as noted, though it is

debatable as to which year the data on the map represents.

Perhaps no one is more

qualified to tell the story about the Whipple family than Kip Whipple,

descendant of one of the earliest families to settle the Mongaup section.

Throughout his long life spent on the hill known as Brown Settlement, Kip

would delight with the opportunity to narrate family lore to any who would

listen. As a story teller, no one surpassed his genius, wit and talent when

recounting tales passed down from his fore-fathers.

According to Kip, his family's American roots began at New London,

Connecticut when his great-grandfather Thomas Whipple and his family

emigrating from England after the American Revolution. Loyalty long being a

Whipple family characteristic, Thomas, who was trained as a physician, was

almost immediately called back to his homeland where an epidemic was

plaguing the countryside, sickening his former patients. His wife and

family, consisting of seven sons, remained to tend to their new home. Thomas

was never to return to his family, succumbing to the disease while in

England

The seven Whipple boys had prospered, all growing to manhood. When the

British again invaded their former colonies at the outbreak of the War of

1812, all seven boys enlisted, taking up arms against soldiers from their

former homeland. Unfortunately, six of the boys died in a battle against the

British. The seventh, son, Thomas C Whipple survived due to the fact he was

allowed to go home on leave so he could hoe his potatoes. After the war, the

remaining Whipple married a sister of Ethan Allen, moved to the headwaters

of the Delaware River in upstate New York and raised eight children, Noah,

Allen, John, Thomas Jr., Ruth, Abigail, Mary Jane and Eunice....

Thomas C Whipple was as

rugged as the mountains surrounding the family homestead. With his naked

hands, Thomas wrestled and subdued a black bear, without injuring the beast.

The bear was so grateful of not being killed that it became a loyal

companion to Thomas, following him around like a pet dog and sharing the

cabin with the Whipple family. So afraid was the rest of the family of the

bear that when Thomas had occasion to go away, the whole family would move

up to the loft of the cabin, leaving the bear in total possession of the

first floor. There the family would remain until the master returned.

Thomas C Whipple and his family moved to the northern section of Rockland

township around 1837, carving out a homestead within the wild forests along

the road from Kingston to the Delaware. Thomas Jr., Noah and John were now

grown men and they too opened the forests and built homesteads in the

clearings they made. The old road past their homes was now beginning to fill

with traffic as more and more settlers came to Rockland. Some stopped and

stayed in the upper Mongaup section, and as the region became populated, it

acquired the name of Brown Settlement.

Soon after arriving from Delaware County, Thomas Whipple Jr., married the

daughter of his neighbor, Christopher Winner. Thomas and Maria raised seven

children; John, Charles, Gideon and Anna, Napoleon, Barbara and Christopher,

the latter who became known as Kip, and in which most of the above can be

attributed. Three years after Kip Whipple's death in 1927, Bob David, a

columnist for the New York Sun spent the summer at the handsome home of

Robert Ward at DeBruce. Ward, the brother of Congressman Ward, was well

familiar with Kip and had been fascinated with old gentleman's witty tales.

The columnist collected many of the stories from Ward and in early

September, 1930, the New York Sun published his column; "A Pilgrimage

Through the Kingdom of Christopher Whipple."

With no evidence found of fencing near the homestead or along the old clearing boundaries, it may be that the Whipple place ceased being used for farming purposes before barb wire became the common practice for fencing animals. Thus, the meadows and pastures have been allowed to grow back into forest for the past century.

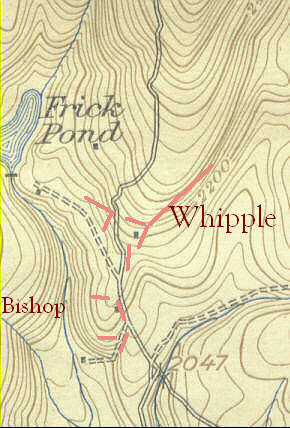

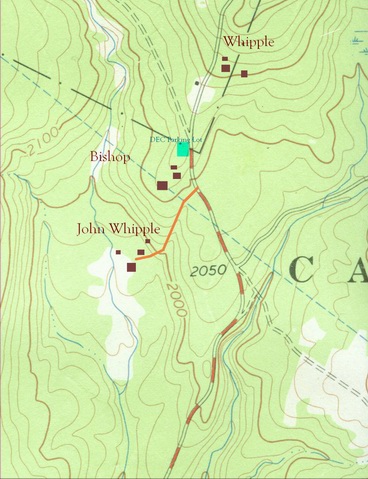

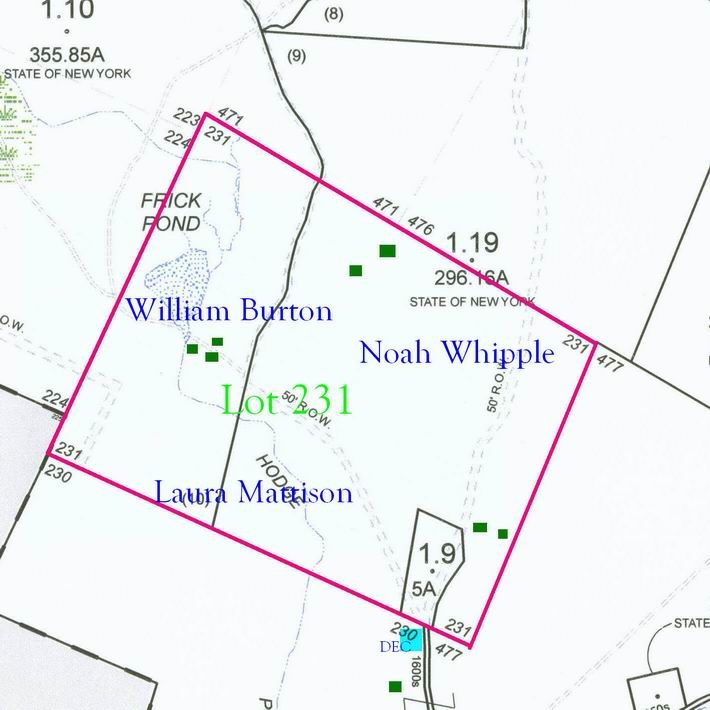

Included is a map showing both the Bishop and Whipple homestead, along with the approximate locations of existing stone walls, evidence of stone walls and rows of deposited field-cleared stones.

Foundation remains appear in three locations on the Noel Whipple homestead, though alterations upon the site make the identification for their purposes uncertain. Unlike other area homesteads, the well has been preserved. Over the years, excavation work has occurred at this particular location but a section of laid-up stonework surrounding a portion of the depression remains, suggesting the site to be the remains of a foundation. A well is found within the depression. The well opening is lined with stones, appears to be in fine condition and now capped by a large clay thimble, probably put in place in later years for safety concerns by either the Boy Scouts or the current ownership, the DEC. Why the site was altered as much as it has been, without destroying or covering up the well is not known. However, with these findings, and the lack of evidence for any other obvious house site in the locale, it is possible that this may have been the original residence, with the well being located within the basement of the structure.

Cut into

the hillside one hundred feet away from the supposed house location,

foundation remains, signifying a small structure, suggest the possible site

of a root cellar. During the year of 1855, Noah Whipple had two acres of his

homestead in cultivation. Like his neighbor David Bishop, one of the plowed

acres was planted with potatoes, which produced 60 bushels. An almost equal

amount of turnips, 50 bushels, was gathered from a three quarter acre patch.

In the remaining one quarter acre, Whipple harvested three bushels of beans.

The large acreage of meadow and pasture supported his herd of cattle, a total of twelve animals. The five milk cows provided milk with a high fat content as three hundred pounds of butter were made during the year.

The

most obvious relict still standing on the Whipple homestead is the remains

of a fireplace. Made out of field stone, the fire chamber is lined with

brick. The chimney, which has since toppled over onto the ground, lay beside

the fireplace. It is also made of field stone and without a clay flue. When

combining the length of the fallen chimney sections and adding that number

with the height of the fireplace remains, the total height of the chimney

suggest that it was attached to a low profile building. There has been some

fireplace and chimney disintegration as can be seen by the stone rubble

surrounding the fireplace, but unless some stones were carted away, there

doesn’t appear to be enough to make much of a difference as to the chimney’s

height. One of the chimney sections appears to be the top of the chimney,

the stonework being capped with concrete.

There is no obvious excavated foundation that adjoins the fireplace, although there is a configuration of stonework that suggests a large building of some sort was located there. The fireplace appears not to be the same vintage as the supposed Whipple foundations, perhaps added later by a conversion or addition of another structure, to accommodate wood choppers or Patrick Flynn’s road workers.

Rubbish that has been discarded, considered worthless at the time it was thrown away, can become invaluable treasures of historical information when rediscovered. The Whipple site and adjoining area is littered with refuse accumulated over the years, most of which that appears to have accumulated since the original homesteaders. Between the Bishop and Whipple places, just off the current DEC trailhead parking lot, can be found a small dump which includes bottles, rusty cans and pieces of metal along with possible farm implements. Household items are strewn alongside the DEC foot trail leading to Hodge Pond, the section that bypasses the old Fred Owens’ cabin. On the Whipple site, the vicinity of the fireplace itself is a field of debris. Items that vary from discarded metal barrels to chinaware suggest multiple uses upon the site.

Many broken pieces of porcelain and glass items can be found, and though most are unidentifiable as to the manufacturer, some items, such as a pitcher, serving tray and glass serving cup appear to be rather ornate. Unfortunately, there are no identifiable printed marks on these items. One item, however, did have a mark. On the back of a broken dish was the mark of Powell & Bishop. A quick online search reveals the Powell & Bishop were British pottery and ceramic makers. Though the partnership had in operation for many years, the name of Powell & Bishop only applies between the years of 1867 to 1878. Items made before and after this period would have had a different mark.

So the question is, how did this dinner plate, probably made around 1870, find its way from England to the forest homestead of Noah Whipple? Did it belong to the Whipple family, or could it be part of the china collection used at Patrick Flynn’s estate up on Hodge Pond?

A third set

of foundation ruins are located in the vicinity of the Frick/Hodge Ponds

tail head DEC parking lot. Fifty yards before reaching the parking area, at

the base of the hillock where the Bishop homestead is located, an abandoned

road can be observed to the left. Cordoned off by large boulders to prevent

vehicular traffic, the trail winds down the hill a quarter of a mile to the

valley floor. At the trail’s final turn, the surrounding forests yield to

old clearings, now overgrown with younger vegetation. The numerous

foundations and stonewalls note the homestead of John Whipple.

A third set

of foundation ruins are located in the vicinity of the Frick/Hodge Ponds

tail head DEC parking lot. Fifty yards before reaching the parking area, at

the base of the hillock where the Bishop homestead is located, an abandoned

road can be observed to the left. Cordoned off by large boulders to prevent

vehicular traffic, the trail winds down the hill a quarter of a mile to the

valley floor. At the trail’s final turn, the surrounding forests yield to

old clearings, now overgrown with younger vegetation. The numerous

foundations and stonewalls note the homestead of John Whipple.

Attached is

the Sullivan County Atlas of F W Beers, published in 1875, showing the

Mongaup portion of the Town of Rockland. The Atlas is a valuable historical

tool not only for its accuracy but also for signifying the location of

residents during that period. However, perhaps because of the isolated

nature of the area, the landmarks depicted at Mongaup appear only to be only

an approximation as to location of roads and residences. Adding to the

confusion is the fact there are no deed of ownership by these homesteaders

registered with the Sullivan County Clerk, as the total area was owned by

Henry Low.

Attached is

the Sullivan County Atlas of F W Beers, published in 1875, showing the

Mongaup portion of the Town of Rockland. The Atlas is a valuable historical

tool not only for its accuracy but also for signifying the location of

residents during that period. However, perhaps because of the isolated

nature of the area, the landmarks depicted at Mongaup appear only to be only

an approximation as to location of roads and residences. Adding to the

confusion is the fact there are no deed of ownership by these homesteaders

registered with the Sullivan County Clerk, as the total area was owned by

Henry Low.

Low was a powerful figure in Sullivan County. A Monticello attorney and judge, Low became the representative for the Sullivan County district in the New York State Assembly. During his time at

Albany, legislation was passed, partly due to his instigation, authorizing the construction of the Oswego and Midland Railroad and the location of its route passing through the center of Sullivan County. Low became one of the principle officers for the railroad company and realizing the potential prosperity for the areas along its route, he purchased large tracts of land from the heirs of John Hunter, descendant of one of patentees of the Hardenburgh Patent. These lands were already populated with tenant farmers, so Low became the landlord, and remained so until he began selling the homesteads during the 1890’s.

As for the map, the “J H Whipple” homestead is probably the location of the foundation ruins that are found along the valley below the current DEC parking lot. There are two unmarked residences located along the dead-end road. The positions in relation to the road seem to suggest that the first residence would be that of Noah Whipple. The second, at the end of the road, will be discussed later.

John

Henry Whipple was the son of Thomas C Whipple. When, during the fall of

1861, the nation called for volunteers to enlist into the army to preserve

the Union against the southern secessionists, both the twenty-year-old son

and his forty-seven-year-old father enlisted on the same day, joining the

ranks of the 56th New York Infantry Regiment. Both father and son

served throughout the duration of the war.

Returning from the war, Thomas and his wife lived with her aged parents while John, now twenty-four, along with his four brothers, ranging in age from twenty-two to sixteen, are listed in the 1865 census as residing separate from the parents. During this time, he married Elizabeth Burton, and resided on the homestead until at least 1875. Within five years, however, John and Elizabeth had moved to the Claryville area in the Town of Denning, Ulster County.

The foundations on the John Whipple homestead are in relatively good condition. Little, if any, alterations can be found on the site. At the residence, the steps leading to the back entrance into the cellar can still be treaded upon. Stonework along the front of the foundation suggests that a porch was located along the length of the building. Pieces of clay tile, used for a chimney flue, along with segments of concrete block were found, suggesting a chimney may have been constructed or reconstructed later. The well was not found.

Though the well

was not found, there is evidence that one did exist. Found along the wall

near the barn’s foundation was a large cast iron object bearing the

inscription “Downs & Co, Seneca Falls” molded upon the surface. The name

signifies the name of the company whose foundries forged numerous cast

products, which included water pumps. This upstate manufacturing company

continued operations under the name of “Downs & Company” until 1869, when

the company then became known as Gould’s Manufacturing Company. The object

appears to be the bell-house portion from such a pump. The threaded portion

on the top would be where the handle and spout would be attached.

Assuming that the pump is an artifact from the original homestead, the date associated with the manufacturer’s name molded on the bell-house roughly coincides with John Whipple’s return from the Civil War, and perhaps the time when this homestead was begun.

Besides the stone walls, remnants of barb wire fence were found buried in many trees at the John Whipple place. Fencing of this sort was not found at the other homestead locations. Use of barb wire as fencing became popular during the 1880’s, the wire and barbs changing in form over the years. Two different types of fencing can be found in trunks of trees along the stone walls and at the base of the road leading onto homestead. This difference in fencing indicates different periods when the wire was manufactured, and possibly approximate times when the fence was strung.

Though both fences are made up of two

strands of wire twisted together, the barbs and how they are attached to the

wire are different. Early fencing made in the 1880’s consisted of barbs

attached to one strand of wire, then a second strand twisted around the

first to keep the barb in place. Many pieces of this style of fence can be

found along the walls. The barb itself has only two wraps around the single

wire and only has two points.

The second type fence again is made of two strands of wire twisted together, but the barbs are twisted around both strands instead of the one. The barbs on this fence are also different, having four points instead of two as well as four twists around the wire. Though the ages of the either fence are hard to determine without actually cutting down the trees, the four-point barb fence appears younger than the two-point barb wire judging on the amount of disintegration on both types of fences. The existence of these fences on the John Whipple place, and the lack of evidence of wire fencing at the other locations, indicate that the former homestead was probably still in use well into the early twentieth century, long after the others were abandoned.

![]()

The road

leading to the John Whipple homestead begins one hundred yards before

reaching the DEC trailhead parking lot. Following alongside a narrow glen,

the trail has been carved out of the valley’s side wall, making a

well-defined passageway through the forest until the valley opens into the

wider, flat expanse of the Hodge Pond brook valley and the Whipple

foundations. It is apparent, however, that this road was not the original

route down to the homestead for a stone wall near the mouth of the glen has

been broken open to allow the road to pass through.

Even with the

rocks cleared from the road located at the bottom of the glen and laid-up

alongside forming what is now the remains of a stone wall, passage over this

narrow trail was most likely a bone-jarring, wagon busting experience.

Possible evidence of the road’s rugged condition may be in the fact that

remains of two wagon wheels were found along the old roadway.

The original road leading to the John Whipple homestead runs parallel with the current trail, but at the bottom of the narrow glen. Stone wall remains follow alongside the road, helping to delineate the road. These walls may be associated with the David Bishop homestead, which was located along the upper portion of the glen. It is also here that the wall and evidence of the road, for some reason, leave the valley floor and curve up the hillside.

The

early history of the land settled by these early homesteaders can be

deciphered by “reading” the surrounding landscape. Long before the Whipple

family migrated to Mongaup’s virgin forests, long before Indian braves from

the Lenape nation stalked the bountiful deer and elk that roamed throughout

the Catskills, in fact, long before man from any of the ages set foot into

the upper Willowemoc valleys, glaciers diving southward from the frozen

northern climate penetrated these hills and valleys, modifying the original

landscape, leaving behind landforms altered by glacial scouring and debris

deposition.

Twelve thousand years ago when the continental glacier covered the highest peaks of the Catskills, lobes of glacial ice crossed over the Beaverkill-Willowemoc watershed divide above the Mongaup territory. Flowing southward, these lobes either stalled as the climate became warmer, or met resistance from remnants of the Willowemoc valley glacier. The debris deposited by the stagnant glacier choked the Mongaup territory valleys with soil and rocks, altering the course of south-flowing streams and brooks and damming bodies of water behind the ice and piles of debris. The depressions behind these dams filled with water, forming ponds until the dam was breached by the pond’s overflow, cutting new channels within the glacier debris as the water flowed over and down the dam.

One of the basic principles taught during high school geology is that river erosion will form V – shaped valleys. The glen that leads to the John Whipple homestead has been eroded into this V-shape configuration, however, there is currently no brook, stream or river flowing through the glen, nor has there been for some time. Ten thousand years ago, the mound of glacial debris and ice choked the valleys, altering the course of streams and brooks flowing from the Mongaup Pond section. A new course was found as it breached the debris and ice, flowing down the dam and cutting a new channel. Eventually, as the ice continued its retreat northward due to the warmer climate, a new overflow channel breached the glacial debris becoming the pond’s new outlet, the earlier channel becoming abandoned and left high and dry. This ancient streambed would later be used as a natural passageway down to the John Whipple homestead.

In 1893, the

trustees for the Henry Low estate sold to the homesteaders the property that

comprised the tenant farms. Since the homesteaders had never ownership of

the meadows and pastures of their farms, actual legal boundaries were never

needed. When deeds were drawn up, descriptions as to the location, property

lines and acreage of the lots were vague, often accurate information being

non-existence. In some cases, deeds were described only as being within

certain Hardenburgh Patent lots, referring to those lots configured a

century before during the original Hardenburgh survey.

In 1893, the

trustees for the Henry Low estate sold to the homesteaders the property that

comprised the tenant farms. Since the homesteaders had never ownership of

the meadows and pastures of their farms, actual legal boundaries were never

needed. When deeds were drawn up, descriptions as to the location, property

lines and acreage of the lots were vague, often accurate information being

non-existence. In some cases, deeds were described only as being within

certain Hardenburgh Patent lots, referring to those lots configured a

century before during the original Hardenburgh survey.

The lot that contained the Noah Whipple homestead, lot number 231, is an example of the ambiguity of property ownership resulting from tenant farming. The Noah Whipple farm was described as being the northeast portion of the lot and containing 75 acres. That's all. The deed for Laura Mattison described her property as being the southern portion of lot 231, containing 100 acres. Again, that's all. The William Burton place was located by deed description as being the northwest portion of the lot; no acreage given. Perhaps well-defined deeded descriptions for these particular properties were not needed in 1893; Laura Mattison and William Burton’s wife, Julia Ann, were both the daughters of Noah Whipple. As for the seventy-year-old father, he was suffering from cancer and would be dead within a year.

Old,

abandoned foundations catch our attention, as well as our imaginations.

What type of building did the walls support? Was it a house, a barn,

a mill or some other structure? Who were the people that built it and why?

As the years have gone by, the wooden buildings have long since rotted away,

leaving behind crumbling stone walls, burying any evidence of the

foundation’s purpose amongst caved-in debris. Likewise, memories have become

faded or carried to the graves of those who may have known, leaving behind

questions as to the foundation’s origins that may never be answered. One

particular foundation-ruins amongst the early Mongaup homesteads is unique

for located within its veiled walls can be found an unusual marker; unusual

for being in such a remote area. In just the few simple engraved words, this

marker becomes the narrative for the foundation's history.

Old,

abandoned foundations catch our attention, as well as our imaginations.

What type of building did the walls support? Was it a house, a barn,

a mill or some other structure? Who were the people that built it and why?

As the years have gone by, the wooden buildings have long since rotted away,

leaving behind crumbling stone walls, burying any evidence of the

foundation’s purpose amongst caved-in debris. Likewise, memories have become

faded or carried to the graves of those who may have known, leaving behind

questions as to the foundation’s origins that may never be answered. One

particular foundation-ruins amongst the early Mongaup homesteads is unique

for located within its veiled walls can be found an unusual marker; unusual

for being in such a remote area. In just the few simple engraved words, this

marker becomes the narrative for the foundation's history.

The trail to Frick

Pond from the DEC parking lot is a relatively easy one-half mile woodland

saunter along an old, abandoned road. Along the way, sections of neglected

and crumbling stone walls can be seen alongside the trail, evidence that

what is now grown forest were once open fields. Just before reaching the

pond, the hardwood forest yields to an overgrown field filled with high

brush, thick raspberry brambles and old apple trees. This is generally known

as the Frick place, but the particular circumstances of Benjamin Frick’s

short tenure on the old homestead, and the evidence of fields, foundations

along with the remains of a large dam at the pond’s outlet suggest

homesteading existed here for a much longer duration.

The trail to Frick

Pond from the DEC parking lot is a relatively easy one-half mile woodland

saunter along an old, abandoned road. Along the way, sections of neglected

and crumbling stone walls can be seen alongside the trail, evidence that

what is now grown forest were once open fields. Just before reaching the

pond, the hardwood forest yields to an overgrown field filled with high

brush, thick raspberry brambles and old apple trees. This is generally known

as the Frick place, but the particular circumstances of Benjamin Frick’s

short tenure on the old homestead, and the evidence of fields, foundations

along with the remains of a large dam at the pond’s outlet suggest

homesteading existed here for a much longer duration.

This was probably the homestead of William and Julia Ann Burton. Due to the lack of records and accurate maps and deed descriptions, just when the homestead was established is unknown. Julia is the daughter of Noah and Katherine Taylor Whipple and married William in 1860. The Beers Atlas of 1875 bears some inaccuracies at this section; lot boundaries are not true, some lot numbers are incorrect and two residences are unnamed. It is therefore quite possible that the Burton family were residing at one of these un-named locations. However, it wasn’t until 1893 and the fire-sale of Henry Low’s estate that William and Julia’s name appears on any deed, and even then with only a vague description of their property. The Burtons sold the farm to Benjamin Frick in 1901.

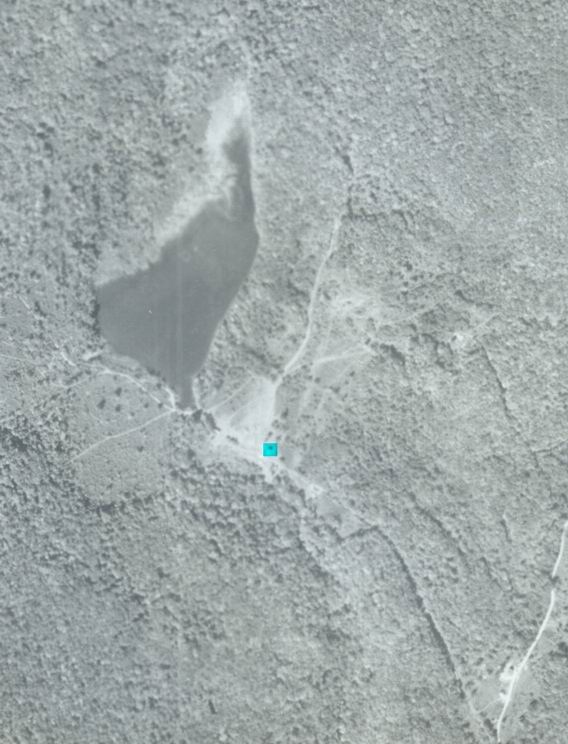

Included is an aerial photograph of the Frick Pond area, probably dated from the late 30's. The clearing near the center of the image would be the Burton homestead. One building was still standing at the time, which is highlighted.

1850-60