Livingston Manor WWII Honor Roll

<click picture for larger image> 3/30/2008

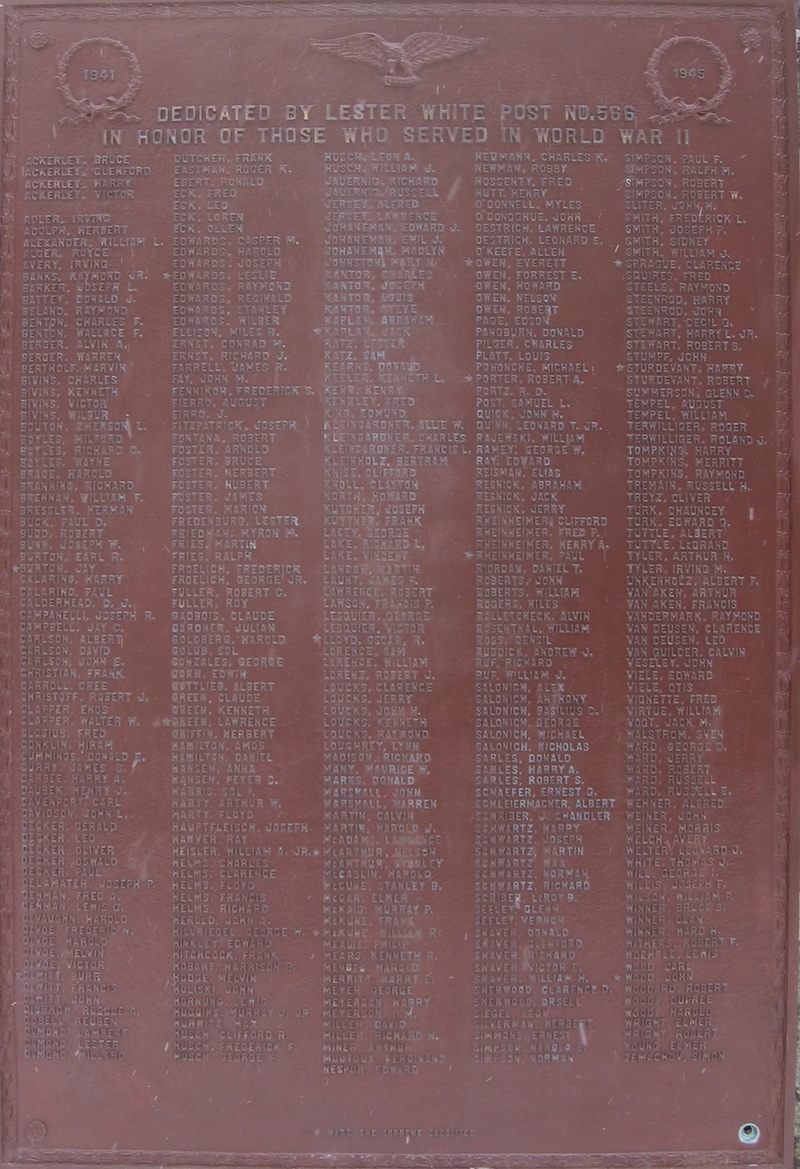

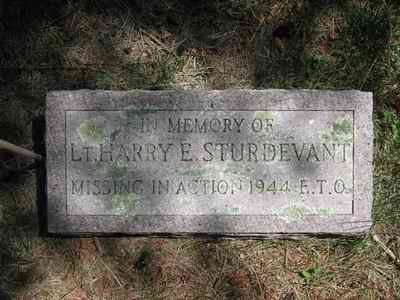

In 1954, this "honor roll" list of World War II veterans, consisting of all 390 names of those who served in the armed forces, were placed on the bronze tablet set in the granite stone, and dedicated at its present location in front of the American Legion Hall. The two new additional names that were not included on the earlier memorial were those of Leslie Edwards and Harry Sturdevant. Fred

The 390 names of those who served in the

armed forces during World War II inscribed upon the "Honor Roll" tablet in

front of the Legion Hall represent the families of our locality, some with a

long history within the area and others who happened to be planted in the

Manor at that particular time. But like the trains that pulled in and out of

the Manor station, other families, whose sons and daughters also served,

came and went. Often, members of the families were associated with the O&W,

moving wherever the railroad job opportunities existed. Others worked in the

local factories and mills, which when the local resources dried up and the

businesses closed-up shop and moved, so often did the workers. But no matter

where these families wound up, war department telegrams delivered the news

of the fate of their loved ones, and the sad news filtered back to friends

and relatives back here at the Manor.

One early family, the Harringtons, who were one of the earliest residents on

DuBois Street, left the Manor when the father died, the son answering his

nation's call. The young Sweeney boy graduated from the local high school in

1931, realizing his dream of becoming a teacher. The young minister from the

Presbyterian Church gave up his exemption and enlisted into the army in

1942. So did the son of a former pastor of the Methodist Church. The Dayton

family, now considered a Manor family, was not the case when the tablet's

Honor Roll was assembled. The Mulvey boy also was not included.

Telegrams from the War Department, informing the families of those soldiers

who were wounded in action, missing in action or killed in action, were few

during the first two years of the war, but with the allied offensive of

1944, they became more numerous, often on a weekly basis. The geographical

names of the locations, from both war fronts, of these boys' deaths would

later become familiar to us all; the bridge-head at Remegen, The Bulge,

bombing raids over Hanover, the sands of Iwo Jima. Two Gold Star mothers'

sons survived the invasion of Normandy. Though wounded, they lived, and

died, to fight another day.

The "Honor Roll" of all those Manorites who served during this conflict fill

the three by four foot bronze tablet with their names. Most came home after

the war, resuming their lives. The supreme sacrifice made by the few young

men who did not return is noted by a lone star placed before each of their

names. - Fred

In reference to the posting about about those from the Manor who served in WWII, I would like to know if any of those who died in the war were fathers and left children behind? I belong to a group called the American WWII Orphans Network (www.awon.org). Among the many things we are doing is putting together a database of all known fathers who were KIA or are still MIA. It is estimated that there were 175,000 American orphans created by WWII. - Kathy

Oscar Lloyd had a son. Most of the other

13 local veterans who died during the war and listed on the "honor roll"

were unmarried, except for Jack Kaplan and John Wood. Wood had just been

married in '42 and had just visited home on furlough in '44 before being

sent back over to Europe. Whether either one of these boys had children born

after their death is unknown.

Kenneth Sweeney

Ken Sweeney was about thirty years old at the time of his death, and was a teacher on Long Island. Whether he was married and whether he had any children is unknown. - Fred

Kenneth Sweeney

Letters from Kenneth F. Sweeney More information about Kenneth and a student he became involved with

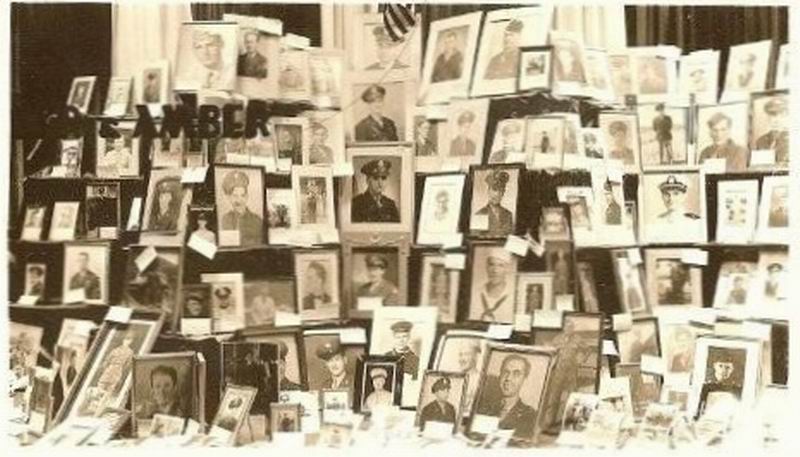

Amber's WWII Display

|

John S. Wood

John S. Wood was one of the more popular young men of Livingston Manor,

and somewhat of a legend to those who still remember him. John, popularly

known as "Gus", was the son of a carpenter, Clayton Wood and his wife

Joanne, the family coming from Readburn, in Delaware County, to Livingston

Manor in 1921 when Gus was 13 years old. He was a talented athlete,

excelling in baseball and basketball. Throughout high school, he teamed up

with his brother, Leonard and Jake Vogt for Livingston Manor High's

successful seasons on both on the diamond and court.

After graduating high school in 1927, Gus continued an athletic career by

playing in, and eventually organizing the local semi-pro leagues, playing

teams from Orange, Ulster, Delaware and Sullivan counties. The same trio

that excelled during high school, Gus, Leonard and Jake, were again the

nucleus for these semi-pro teams, such as "The Island Five," "Livingston

Manor Big Five," "Sullivan County Giants" and "The Livingston Manor

All-Stars. These popular teams had a large local following that filled the

bleachers with overflow crowds. Other players from the Manor who played on

these teams were Vincent Knoll, Russ Hodge, Dutch O'Keefe, and Leonard

Welter.

Gus also enjoyed the outdoors. Gus, along with Jake and Lou Kannigeser were

known for their adventures with rifle or rod, often coming back from an

excursion with more stories than game. Once, while suckering through the ice

at Louck's pond above Parkston, Gus had made a "drive" that had Jake and Lou

with all they could handle pulling the finned creatures through the hole.

That night, all their families, relatives, friends and neighborhood cats

feasted on the day's catch, nobody doubting the supposed method of their

catch.

Gus worked as a chauffeur, sold real estate and, immediately after high

school, began work as a clerk in the Sprague-Krom Company store where he

soon became the store's manager.

Frances Hitchings began her elementary teaching career at the Livingston

Manor school in 1931 and immediately became the apple of Gus' eye. Their

courtship lasted over a decade until October 31st, 1942, when the couple

were married. Three months later, Gus was inducted into the service.

Frances Hitchings began her elementary teaching career at the Livingston

Manor school in 1931 and immediately became the apple of Gus' eye. Their

courtship lasted over a decade until October 31st, 1942, when the couple

were married. Three months later, Gus was inducted into the service.

Gus transferred from the Army to the Army Air Force and trained as a gunner

and engineer for B-24 bombers. Just before he was to go overseas, in March

of 1944, the pilot of his crew became ill, affording Gus the opportunity for

a quick trip back home to see his new bride. The furlough was short and at

the end of the month, Gus and his crew were sent overseas, joining the

Fifteenth Army Air Force in Italy.

Gus Wood was the ball turret gunner of the ten-man crew aboard the B-24, the

Suzan Jane, piloted by Lieutenant Norman Lawrence, attached with the 717th

Bomber Squadron of the 449th Bomber Group. The operating base for the 449th

was the Italian Air Force base at Grottaglie, in southern Italy liberated by

the Allied invasion and occupation of the lower peninsula in 1943. This

field, along with others, gave the Fifteenth Army Air Force access to

military targets in southern Germany and Austria, targets unreachable from

the heavy bombers flying from across the English Channel.

In the early dawn light of May 29th, 1944, thirty-eight B-24 Liberators

lifted off from Grottaglie for a mission against the industrial complex at

Wiener-Neustadt, Austria. It was the 29th mission for the crew of the Suzan

Jane, piloted by a substitute pilot Frank Henggeler. Over the target, the

bomber formation encountered a wall of flak from ground anti-aircraft guns,

heavily damaging the Suzan Jane. Henggeler was unable to keep up with the

formation, falling behind, when a Luftwaffe Messerschmitt piloted by Major

Redlich came upon the stricken aircraft firing its cannons upon it. Inside,

the radio-man was killed and two gunners wounded. The ball turret, hanging

below the belly of the plane, was blown away, killing Gus Wood. Observers

noted afterward that as the Suzan Jane plunged into a fiery crash outside of

the village of Furth, Austria, eight parachutes slowly trailed behind. As

for Redlich, his Messerschmitt crashed during the engagement and he was

listed as killed in action.

On June 15th, 1944, Frances Hitchings Wood received a telegram from the War

Department notifying her that her husband was listed as missing in action.

In July, she left her Jacktown home returning to her hometown of West

Winfield where she received word that the German government recovered Gus'

body and turned it over the Red Cross. Frances received the Purple Heart

that was awarded posthumously to her husband. Gus' short furlough in March

would prove to be his last trip back to the Manor, for his remains are

interred at Ardiennes American Cemetery, Neupie, Belgium. - Fred

Livingston Manor Times - September 6, 1944

One of the features of an Army Air show at Rome, New York, August 1st, was

the presentations of awards to the next of kin of Army heroes. Included

among them was Mrs. Frances S, Wood of West Winfield, who received the

decoration awarded to her husband, the late Staff Sergeant John S. Wood of

Livingston Manor, killed on an air raid over Germany. The citation signed by

J.A. Ulio, Major General, reads as follows:

"I have the honor to inform you that by direction of the President, the Air

Medal and two Oak Clusters, representing two additional awards of the same

decorations, have been posthumously awarded to your husband, Staff Sergeant

John S. Wood, Air Corps, for meritorious achievement in aerial flight while

participating in sustained activities against the enemy between the days of

April 3, 1944 to April 13, 1944; April 16, 1944 to April 24, 1944; and April

24, 1944 to April 28, 1944." - Fred

Gold Star - Henry E. Owen

Lena

Stahle immigrated from Switzerland to America in 1892 when she was eighteen

years of age. Within a year she became a citizen of her newly adopted

country and met Henry Owen, native son of Livingston Manor. They were

married in 1893 and moved onto a farm above the community of Emmonsville

(Grooville).

Lena

Stahle immigrated from Switzerland to America in 1892 when she was eighteen

years of age. Within a year she became a citizen of her newly adopted

country and met Henry Owen, native son of Livingston Manor. They were

married in 1893 and moved onto a farm above the community of Emmonsville

(Grooville).

The large tracts of forest that surrounded the upper valley of Sprague Brook

were ideal for the relatively new industry of extracting chemicals from the

burning of hardwood. John Emmons, from Binghamton, was a pioneer in the wood

chemical business and in 1882 built two wood chemical factories, one at

Morsston Depot and the second along Sprague Brook. Within a short time, the

community that developed around the factory increased from three families to

sixty families, providing the workforce for not only for the Emmon's

factory, but also for the lumber mill that set up nearby. When Emmons died

in 1888, Stoddard Hammond Jr. took over the business. with dwindling

resources and transportation issues, Hammond closed down the factory in 1897

and removed the equipment to his Pennsylvania plant. Hammond himself

remained in the area on one of his tracts of land, creating Orchard Lake, a

one hundred acre lake which was stocked as a fish hatchery, the largest in

the county, and erecting a large guest house, four stories high and

overlooking the lake, which his wife ran as a summer boarding house.

Lena and Henry Owen's farm was located along the upper access road leading

to the Hammond resort, where Lena worked as their cook. In 1911, Henry

developed a sore on his upper lip which proved to be cancerous. The tumor

was removed but complications set in after the operation resulted in blood

poisoning. Henry died two weeks after the operation at the age of 47,

leaving Lena alone with the responsibility of raising their family of eight

children, the youngest being just a nine-month old baby, Everett H. Owen.

Hard times and tragedy always seemed to be a part of Lena Owen's family. In

1919, thirteen-year-old Bert Owen, like his father, entered the hospital for

an operation, and like his father, succumbed to complications after the

surgery. Fern Owen, twenty-two year old brother, married Dorothea Dutcher in

the spring of 1927. Within two months of the wedding, Dorothea became ill

and died.

The next winter, the evening of December 6th, 1927, Fern Owen was driving

his Ford sedan along with his older brother, Fred, returning from a visit to

his wife's parents who lived on Cottage Street, across the railroad tracks

from Roscoe. With the lack of eyewitnesses, the details were never known of

how it happened, but the Owen car either stalled on the tracks at the

Cottage Street railroad crossing, or Fern attempted to outrun the northbound

"Scoot". Due to the darkness of the evening and the position of the engineer

in the locomotive, Fern's car was never noticed on the tracks in front of

the train until the impact of the collision was felt. Fern was found

unconscious within the wreckage, dying of his injuries within the hour while

Fred was seriously injured, though he survived the accident.

Lena Owen remained at the Owen farm, working as the cook for the Hammonds

and the subsequent owners, the Trout and Skeet Club, until 1927, when she

and her youngest son, Everett, moved into the house next to the creamery on

Mott Flat, north of the Manor. Everett remained with his mother, assisting

and caring for her as her health began to slowly fail, until he was drafted

into the US Army in April of 1941. While he was stationed at Fort Jackson,

North Carolina, Everett received notice that his mother passed away on

September 29th, 1941. Lena outlived her husband and four of their ten

children. She lived as a widow for the last thirty years, independent and

industrious, centering her life around her remaining children.

Everett Owen achieved the rank of sergeant, a member of Company A, 28th

Infantry Regiment. While stationed at California, he came home on furlough

in August of 1943 when he admitted to friends that he liked the Army, as

well as California, but that he also enjoyed coming home and seeing his old

friends. The 28th Regiment left New York City on December 5, 1943 for the

European conflict.

Everett Owen achieved the rank of sergeant, a member of Company A, 28th

Infantry Regiment. While stationed at California, he came home on furlough

in August of 1943 when he admitted to friends that he liked the Army, as

well as California, but that he also enjoyed coming home and seeing his old

friends. The 28th Regiment left New York City on December 5, 1943 for the

European conflict.

The 28th Regiment, part of the 8th Division, landed on Utah Beach, July 4th,

1944 and participated in the Allied Army's struggle in the hedgerows of

Normandy until finishing off the last pocket of German resistance at the

city of Brest. Meanwhile, the rest of the Allied Army raced across France

toward Germany in the summer of '44 until they over-extended their supply

lines. With the Allied Command decision to concentrate an attack in

September towards the Netherlands and diverting supplies for that mission,

the rest of the Allied Army sat relatively idle until it could be

re-supplied, allowing the German army to re-organize and strengthen their

line along the German border. Along this line of defense are the hilly,

heavily wooded areas surrounding the German village of Hurtgen.

The Hurtgen Forest was defended by a determined German army, depleted of its

regulars and manned by new recruits, rushed into service to defend the

homeland. Barbed-wire, land-mines and artillery would make this upcoming

battle the most contested piece of land within the German homeland during

the entire war. The American Army's 28th Division slammed into the forest on

November 2nd, but the difficult terrain, German counter-attacks and the

ceaseless bombardment of artillery fire crippled the attackers with heavy

casualties. Its fighting capacity diminished, the 28th Division was replaced

with elements of the 8th Division on November 16th, including Owen's

regiment. On the 24th of November, Company A of the 28th Regiment was sent

forward to replace the front line regiment when it ran into a heavily mined

field. After the field was cleared, their forward progress was again checked

by heavy artillery fire, forcing what remained of the company into hastily

dug foxholes for the rest of the day. The next day, Company A again moved to

new forward positions, again with the same results. Clinging to their

forward line of foxholes, volunteer carrying parties were established,

bringing supplies up to the front lines and returning with the casualties.

It was dangerous work, the carrying parties crossing previously contested

terrain, denuded by previous artillery fire, and were easy prey for the

German guns, receiving heavy casualties amongst their own ranks....

Mrs. Erlene Lare and Mrs. Mildred Hodge of the Manor, sisters of Everett

Owen, first received word in December that their brother was listed as

missing in action but soon a telegram was received from the War Department

the first of the year informing them that Everett was killed in action on

November 26th, and that he was buried in a temporary military cemetery in

Belgium.

It was almost five years later before Everett returned home. In early July

of 1949, the transport Carroll Victory brought the remains of Everett, as

well as over 3,300 other World War II dead soldiers, back from their

European graves to be returned to their families. Everett returned to the

Manor with a military escort and on August 1st, 1949, Sergeant Everett Owen

was laid to rest with full military honors at the Orchard Street Cemetery.

As much as Everett liked the army life, he also enjoyed coming home to be

amongst his friends. Everett finally came home and is again amongst his old

friends. - Fred

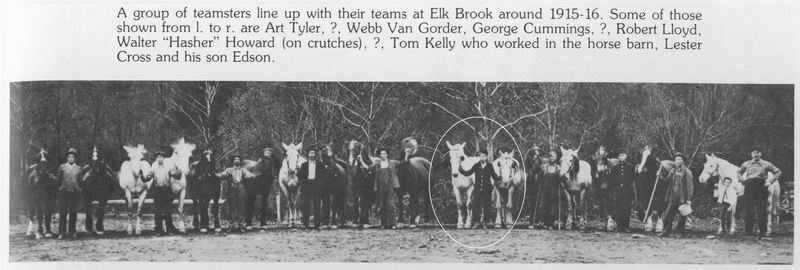

Oscar Lloyd

Oscar Lloyds Father Robert Lloyd around 1915 at Elk Brook Acid Factory

Oscar was killed in WWII

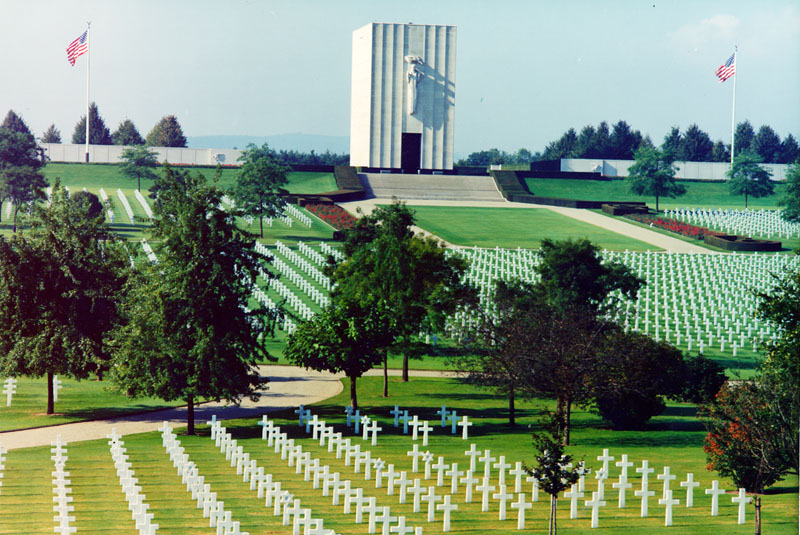

Oscar Lloyd is buried in the Lorraine American Cemetery at St. Avoid, France

The Lloyd family and the Hazel Acid Factory

The end of World War I brought on the beginning; the

beginning of the end of the wood chemical industry. Before the war, the

chemical products produced by the burning of wood was beginning to be

replaced by synthetic substitutes, but since the conflict created the need

for these products which were used as components for explosives and wood

alcohol, demand was up and the local factories were once again prosperous.

Of the local factories, Thomas Keery's plants were to have an advantage as

they were located along the Ontario & Western Railroad. At the Hazel

chemical factory, a track siding connecting to the O&W main line, offered

the company easier access to the railroad transportation network and less

handling of the products. When the wartime demand was over, and natural

resources becoming depleted, smaller companies either closed or suffered

devastating fires. As competition lessened, the Keery plants continued to

prosper, somewhat, though this prosperity was not necessarily shared with

the company's work force.

At Hazel, drab dwellings were erected to house families of the factory

workers. Other employees, including factory workers, wood-choppers and

teamsters, made their residence in the boarding house run by the plant's

manager, Elmer Knapp. The families came from upstate New York, Delaware

County and from Pennsylvania. Most of the men were experienced in the

chemical business and had worked at other factory locations, often in a

Thomas Keery plant, which at one time were numerous throughout the upper

Delaware River valleys. The work was long, hard and dangerous, but these

folks, especially during the years before the outbreak of the Second World

War, felt fortunate to have work. The pay was meager; a weekly paycheck of

$13 during this period was common, most of which went for supplies at the

Keery company store. They were poor, and even though they had work, they

would remain poor until they moved out, which was often to just another

factory community.

The biggest fear for these folks was the closing of the factory. A fire at

one of these factories would be devastating, not only to the factory's

owners, but to the families that it supported. Early in the morning of

January 26th, 1925, the chemical factory of G.H. Treyz at the community of

Willowemoc was discovered to be on fire. The large, one-story, metal

covered, frame building was completely consumed by flames, leaving only

embers and twisted sheet metal in its wake. The twenty-five employees who

worked at the factory were immediately thrown out of work, and with the

eventual abandonment of the enterprise, the community never recovered.

Early in the morning of April 27th, 1927, Robert Lloyd, night watchman of

the Hazel factory, discovered flames coming from the building that housed

the oven room. The Hazel plant was considered a modern facility for instead

of buring wood in retorts, as was the practice in the older plants, wood was

loaded on small steel cars and moved on tracks into the oven building where

it was heated until the byproducts were produced. Apparently, the smoldering

wood on one of these cars ignited and set the oven building on fire.

Fortunately, Lloyd discovered the fire soon enough so that the fire was

contained to just the one building, minimizing the damage. It was

immediately replaced with an all steel structure and the plant continued to

operate, to the relief of the workers and their families.

The Lloyd family moved to the Livingston Manor area in 1912. The family's

origins, during the mid-nineteenth century, were at Cooperstown, Otsego

County, where the family began its odyssey of following the acid factory

trail. Oscar Lloyd worked at the original Keery factory located at

Keerysville, in Delaware County, where his son, Robert Oscar Lloyd was born.

Robert Oscar Lloyd migrated to the factory town of Elk Brook, along the

waters of the lower Beaverkill, and worked at the acid factory of Arthur

Leighton. His son, Robert Jr., worked at the Leighton plant as a child,

until, at the age of 20, made the move to Hazel, and work at the Keery

plant. He married Gussie Knox, a Port Jervis girl, and together had four

children, three of whom survived. William Oscar Lloyd, known as "Oscar", who

was the oldest, was born on August 10th, 1920, followed by two sisters,

Virginia in 1922 and Lida in 1926

By the mid thirties, competition from the synthetic

chemicals coupled with the depressed economy, shut down the smaller and

unproductive wood chemical plants throughout the upper Delaware River valley

region. Those few that survived, including the Keery factory at Hazel, went

for long periods where the plant ceased operations, creating severe

hardships on those families already accustomed to a hard life. The families

living in company houses paid a monthly rent of $7, and without the plant

operating, were required to pay a $9 monthly bill for home-heating fuel.

Without the monthly income, as slight as it was, credit was soon exhausted

at the company store. The families scrimped and scavenged what they could,

or simply did without.

The plight of the Hazel residents became known when, in January of 1935,

Mrs. Rose Moore, who was suffering from an infection, was taken to a

Monticello hospital. There it was quickly determined that she was suffering

from severe malnutrition besides the blood poisoning. Authorities at the

county seat's welfare office, along with the Town of Rockland welfare

officer, soon discovered that the condition of Mrs. Moore was not an

isolated incident, but rather just the tip of the iceberg of troubles

plaguing the eighty-some men, women and children from the acid factory

community. Besides being malnourished, some families lacked heating fuel,

worn-out clothing could not be afforded to be replaced and many of the

children were without shoes. The children were sent to the Hazel school,

just one half a mile down the state highway from the community, lacking

proper footwear and warm garments. During this era when all suffered from

economic hard times, the crises situation for the the Hazel residents was an

obvious emergency.

When the news of the desperate situation at Hazel made the front pages of

the local newspapers, the folks from Sullivan County responded. Within a

week donations of clothing, food, shoes and toys poured in from all the

county. The Thomas Keery factory, though still remaining closed as it was

being refitted with new equipment, agreed to open the surrounding woods to

the woodchoppers, allowing the idle men to cut four-foot cordwood both for

storage at the Hazel plant or to be transported down the line to Keery's

factory at Cadosia. For all those who were able to swing an axe, cutting

cordwood at $1.25 a cord gave the family a monthly income of over $30, plus

allowing them credit in the company store. Other men found work in

government subsidized programs, the sewer project at Roscoe and the

Conservation Camp that became the Beaverkill Campsite. Eventually the Hazel

factory reopened, but never again operating at its earlier pace, and leaving

many of the folks at Hazel idle, and poor, for long periods of time. Many of

the families, no longer able to depend on the factory for steady work, began

to move out.

The Robert Lloyd family moved out of the Hazel factory house in 1936,

renting an apartment at Livingston Manor. There, young Oscar met Marion

Irene Lyden, daughter of James and Mildred Lyden. Marion's grandparents,

Maggie and John Lyden, conducted a hotel business on Main Street, the old

Robert Bloomer place, that was to become known as the Lyden House, a very

popular social and gathering hall for both the local and traveling public.

James, their son, was responsible for transporting the hotel's guests to and

from the railroad depot. When the family sold the hotel, he continued in the

livery business, serving other area hotels and becoming the caretaker for

the Beaver Lake Hotel above Old Morsston. With the war years approaching, he

found work for the war effort at Newark, New Jersey, moving and remaining

there.

Oscar Lloyd and Marion Lyden were married on November 6th, 1940, at the

Presbyterian Manse at Livingston Manor by the young minister, Reverend

Joseph Harvard. Oscar found work as a laborer and the young couple were

residing in an apartment on Main Street when, on November 21st, 1942, they

began a family with the birth of a son. Robert James Lloyd was the baby's

name, adopting both the names of his grandparents. But soon, the lives of

this family, as well as that of the young minister who married the couple,

were to be interrupted by the drumbeat of the coming war. - Fred

This

is the headstone of Oscar Lloyd's son, found at the Riverview Cemetery in

Roscoe. Birth date Nov21, 1942 and behind the leaves a death date of 1976 - Fred

This

is the headstone of Oscar Lloyd's son, found at the Riverview Cemetery in

Roscoe. Birth date Nov21, 1942 and behind the leaves a death date of 1976 - Fred

Oscar Lloyd was inducted into the service on February 29th,

1944. With the escalation of hostilities on the European war front after the

Normandy invasion in June of 1944, the dire need of manpower, and the rush

to end the war before the approaching winter, new recruits were quickly

rushed through stateside training and into action on the battlefront

overseas. Lloyd spent only four months in infantry training before departing

from New York City to join the 134th Infantry Regiment at England. On July

6th, one month after D-Day, the 134th Regiment, as part of the 35th Infantry

Division, landed on Omaha Beach and by the 11th, was engaged with the

Germans. Throughout that summer and early fall, the Allied army pressed the

German army through France back to the German boarders. Outpacing their

supply lines, along with the severe wet weather during October, the Allied

army was forced to pause in their advance, allowing the Germans time to

strengthen their lines. The 134th regiment was in a defensive position along

the Foret de Gremercy line, near the French city of Nancy, patrolling,

gathering information on the enemy, fighting off half-hearted enemy

counter-attacks and suffering from the relative inactivity through the rain

and chill of the European autumn.

On November 8th, the Allied offensive resumed in spite of the weather. The

134th, initially held in reserve, joined into the fray on the 10th, at first

encountering light resistance. On the morning of the 11th, Armistice Day

from the previous war, the assault battalions resumed their drive until met

by German tanks, offering stubborn resistance and stalling the 134th's

advance. Infantry soldiers, with their light weaponry, were never considered

a match against the heavy guns of enemy tanks, unless they could get within

close range, a risky proposition. Platoons from the 134th stalked the German

armor through the withering blasts from the heavy guns until they were

within ten yards of the tank, close enough to drop grenades into the tank's

turret. Similar stories of heroism were common amongst the 134th that day,

but these acts were not without some cost.

During the first week of December, 1944, Robert and Gussie Lloyd received a

letter from the War Department notifying them that their son had been

wounded in action on November 11th. Little other information was divulged,

the parents not knowing that, in fact, when they received the message, Oscar

Lloyd had suffered for a week with his greivous wounds and had already died

in an Army hospital on November 18th. Upon word of her husband being

wounded, Marion, along with her infant son, moved to the comfort and

sympathy provided at the home of her parents at Newark, New Jersey. There

she received final word, at the end of the month, of her husband's true

fate.

On a knoll overlooing the junction of the Willowemoc and Beaverkill creeks

at the village of Roscoe, is located the community burial ground known as

Riverview Cemetery. Winds whisper through the boughs of the stately pine

trees that reign over the cemetery's inhabitants, perhaps offering solace to

those weary travelers whose life journeys have ended and are laid beneath

these trees. With the end of the acid factory era, the Lloyd family journey

has come to rest in a quiet corner of this cemetery. In simple marked

graves, tended to by descendants, the parents of Oscar lloyd, Robert and

Gussie, lay alongside that of his sister, Virginia. Their son, though, is

not amongst them, for he never returned home from the foreign country he

defended and died for. The journey's end for Oscar lloyd can be found at

plot J, row 25, grave 23, Lorraine American Cemetery, At. Avoid, France.

In the same Roscoe cemetery, along its outside boundary where the brambles

struggle to intrude onto the burial ground, lies a lone grave adorned with

the simplest of headstones. The stone is no more than a well-weathered

boulder, with an inscriptioned hand-chiseled into its surface. The rock's

ledger describes the grave's occupant as Robert Lloyd, accompanied with the

date of November 21, 1942; the date of the birth of Oscar Lloyd's son. The

how and why of the stone and hand carving must be intriguing, though not

known. What is known is that this grave is marked with a memorial marker,

same as the graves of his grandparents, proving that he and his father,

along with the rest of the family, are still being remembered;

"In loving memory of our beloved husband and father, Oscar W. Lloyd, who was

killed in action November 18, 1944;

Loving memories never die,

As years roll on and days pass by.

In our hearts your memory is kept,

Of the one we loved and shall never forget.

Bereaved wife and son"

May 29th, 1947

Livingston Manor Times

Fred

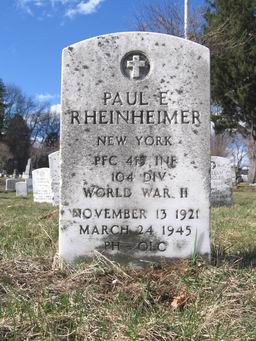

Rheinheimer - On the hill overlooking the

village of Liberty, New York, in amongst the sprawling cemetery that serves

that community, is located the original veterans' cemetery serving the

veterans of Sullivan County. Concentric circles of small, white, marble

headstones, centered by a flag and artillery piece, lie in marked contrast

from the rigidly straight rows of tombstones that make up the rest of the

hilltop burial ground.

Along

the outside circle, facing in a southerly direction where the sun

continuously bleaches the inscribed face of the already white marble, lies

another Livingston Manor son, a member of a popular Sullivan County family.

Along

the outside circle, facing in a southerly direction where the sun

continuously bleaches the inscribed face of the already white marble, lies

another Livingston Manor son, a member of a popular Sullivan County family.

Like so many other early German immigrant families that first came to

Sullivan County during the mid-nineteenth century, the Rheinheimer family's

Sullivan County roots began at Thurmansville, later to be known as Callicoon

Center. Young Henry Rheinheimer, at the age of 26, left the family homestead

outside the village and bought the piece of land owned by Joe Frey on the

hill known as Shandelee. Joe Frey had one of the earliest Shandelee farms,

just below Sand Pond, where he was having the dickens of a time scratching

out a living. As if producing anything off of this hardscrabble lot weren't

bad enough, Joe also dealt with the element of luck, and it wasn't good. For

instance, on January 19th, 1880, Joe bundled up and left his home heading

for work at his woodlot. A short distance away from the house, he happened

to look back and discovered the roof on the building all ablaze. The fire

had gained such headway that when he made it back, there was little he could

have done to save the building, the structure and all its contents were

completely destroyed. Joe was only too glad, when Henry arrived in 1885, to

unload the meager farm and move off of the hill.

Henry first came up with the idea during the summer of 1886, when he

entertained a small gathering of friends and neighbors to a picnic,

providing music for dancing and refreshments. Though it turned out to be a

rainy day, it didn't dampen the revelers' fun as they stirred up quite a

ruckus with dancing, drinking and fighting. It was so much fun, in fact,

that Henry invited them back again that summer. He built a dance floor to

accommodate those high steppers and more people came. He put a roof over the

dance floor to accommodate the revelers and still more people came. He

eventually expanded his house into a large hall and still more people came.

Henry may not have been

much of a farmer, but he sure know how to put on a good time, converting his

ramshackle farm into an entertainment hall. The Rheinheimer place became

known as the Maple Grove Casino, becoming one of the most popular

destinations for entertainment in the area; the celebrations, or "picnics"

as they were called, were advertised as the "Sand Pond Picnic"; and Henry

Rheinheimer became known as "Picnic Heinie".

Henry may not have been

much of a farmer, but he sure know how to put on a good time, converting his

ramshackle farm into an entertainment hall. The Rheinheimer place became

known as the Maple Grove Casino, becoming one of the most popular

destinations for entertainment in the area; the celebrations, or "picnics"

as they were called, were advertised as the "Sand Pond Picnic"; and Henry

Rheinheimer became known as "Picnic Heinie".

Besides not being much of a farmer, he also wasn't much of a business man,

which added to the popularity of the picnics at Maple Grove. Patrons took

advantage of "Heinie's" trusting and generous disposition, weaseling free drinks anyway they could,

using anything that passed for money. Not wishing to argue, "Heinie" seldom

questioned his customers over money matters, thus cutting into his profit.

Unwittingly, though, he extracted his revenge. The foundation space

underneath the casino was used for his roosting chickens as well as for

shelter for his cattle. On dance nights, the stomping on the dance floor

disrupted the flock underneath and with the bright lights shining upstairs,

the birds were attracted into the casino and onto the dance floor. The

chickens, along with the mites and lice that they hosted, mingled under-foot

with the dancing revelers, adding a little more jitter into the dancers'

jitterbug.

trusting and generous disposition, weaseling free drinks anyway they could,

using anything that passed for money. Not wishing to argue, "Heinie" seldom

questioned his customers over money matters, thus cutting into his profit.

Unwittingly, though, he extracted his revenge. The foundation space

underneath the casino was used for his roosting chickens as well as for

shelter for his cattle. On dance nights, the stomping on the dance floor

disrupted the flock underneath and with the bright lights shining upstairs,

the birds were attracted into the casino and onto the dance floor. The

chickens, along with the mites and lice that they hosted, mingled under-foot

with the dancing revelers, adding a little more jitter into the dancers'

jitterbug.

The Prohibition era eventually put a damper on these highly publicized

celebrations. In October of 1918, during the influenza pandemic that was

spreading across the country, "Heinie's" wife, Elizabeth Ranft, whom he had

been married to for thirty years, died. A few months later, during a fierce

spring storm in March of 1919, he was in the barn tending to his cattle when

the gale force wind hit his farm, the building blowing apart, the boards and

timbers crashing all around him. As luck would have it, he was pulled from

the debris and except for scrapes and bruises, was none the worse for wear.

The barn was gone, though, so the animals moved in with "Heinie" into a

portion of the casino. Henry soon remarried, a lady twenty years his junior.

Alice Moore's husband had abandoned his wife and three sons thirteen years

earlier, so the divorcee and widower, he now in his sixty-first year, were

married in October of 1920, the beginning of "Heinie's" second family which

included three sons, Henry, Paul and Fred, along with two daughters, Minnie

and Catherine. Paul E. Rheinheimer, the middle son, was born in 1922.

"Heinie" rebuilt the barn in a rather haphazard way, as was expected, as as

expected, in the fall of 1928, another windstorm blew the structure down.

Again the livestock, which included a team of horses, cattle and chickens,

moved into the dance hall with the Rheinheimer family. Space above the dance

floor served as a haymow, storing the year's cutting salvaged from the

barn's wreckage. During the early morning hours of March 7th, 1929, "Heinie"

was awakened by the smell of smoke which filled his bedroom. Realizing the

danger his family was in, he quickly aroused his wife and children and led

them out of the burning structure. He then went back into the dance hall,

just as the building erupted into a ball of flames, and retrieved the

livestock. Thought was that the blaze was initiated somehow from the hay in

the makeshift haymow, but whether true or not, the hay certainly added fuel

to the fire. With Shandelee shrouded in a misty fog that night, the blaze

covered the whole Shandelee sky with an eerie red glow, the aurora seen for

miles. Firemen ventured into the night, following a moth-like attraction to

the glow, but because of the fog were unable to locate its source as it

slowly disappeared. Neighbors were unaware of the tragedy until the

morning's early light when they came upon the family, huddled together and

being kept warm by the heat of the glowing mound of embers of what was once

their home.

After the fire, the Rheinheimer family stayed on the farm, moving to the

remaining old buildings located below the destroyed structures. Unable to

keep up payments, Henry eventually lost the farm and the family moved to

Youngsville. Young Paul, now a teenager, made his home with the families of

his two sisters, both of whom were now married, Minnie to Adolph Frey of

Youngsville and Catherine to Ernest Schleiermacher of Shandelee. Paul found

work on the farms and boarding houses of Shandelee, keeping close ties to

those Shandelee childhood friends he grew up with. One such friend was Billy

Roser.

William Roser was the young grandson of Henry Roser, a neighbor to the

Rheinheimers. Billy had previously been employed by the town road department

when in early July of 1940, he switched jobs, finding new employment with a

bakery in Jeffersonville. In his pocket was his last paycheck from the town

and on the evening of July 3rd, he and his friends set out to spend it. At

the end of the workday at the bakery, Roser picked up Paul and began an

evening of carousing beginning at the local gin-mill establishments of

Jeffersonville, and then on to Youngsville and Shandelee. Late in the

evening, traveling along the road from Youngsville leading to Shandelee,

with Billy behind the wheel of his old Plymouth he had just recently

purchased, he apparently dozed off, the car climbing the roadside bank and

flipping over on its side before coming to rest against a small concrete

bridge. Both boys were ejected from the vehicle but Paul was the lucky one.

He was thrown onto the traveled roadway and readily found when the wreckage

was discovered. Unconscious, he was carried off to his sister's house just

down the road when his rescuers realized there was probably a second

occupant in the wrecked car. Returning to the scene of the accident, the

rescuers began to upright the car when they, in the pitch darkness of night,

heard moaning coming from the dry creek-bed below the bridge. Billy had been

thrown from the vehicle, over the side of the concrete bridge, landing in

the creek, causing massive head and neck injuries, which soon proved fatal.

Paul's injuries, though severe, healed with time.

Paul Rheinheimer was inducted into the United States Army on October 11th,

1942, becoming a member of the 415th regiment of the 104th Infantry

Division. In warfare, innovative tactics against the enemy would often prove

to be successful if it could exploit an enemy's weakness, or else be an

utter and costly failure. Except for covert operations or artillery fire,

fighting during this war occurred during the light of day. The "Timberwolf

Division", the nickname of the 104th, trained in the deserts and mountains

of Oregon for the unconventional tactic of nighttime attacks. This element

of surprise against the German forces, it was thought, would likely be more

successful in overrunning defensive positions and resulting in fewer

casualties. For almost two years, the Timberwolves trained at one of the

best stateside training facilities, supervised by a commander who realized

the value of hard training in preparing his troops for the rigors of battle.

Weapon firing, squad tactics, scouting and patrolling, detection and removal

of mines, as well as night maneuvers were drummed into each soldier, until

the unit, fit and ready for combat, was deployed overseas to the European

war zone in late August, 1944.

Throughout the invasion of the Normandy beaches in June of 1944, and

immediately afterward, all troops and supplies came ashore onto the European

continent from England, crossing the English Channel to the makeshift ports

built along these same beaches that the Allied Army fought so hard to gain

control of on D-Day. It wasn't until September, when the Americans captured

the French port city of Cherbourg, when Allied ships could unload troops and

supplies at port docks instead of having to be ferried across the shallow

waters of the sandy Normandy beaches. On September 7th, the Timberwolves

became the first division of American troops that landed directly onto

French soil, bypassing England. Their first role was to assist with the

re-supply of the Allied Army, who had become overextended in pursuit of the

German army, until being deployed onto the front lines in Holland during

October.

Though the American Army became bogged down with stubborn German resistance

at Hurtgen Forest in the fall, the 104th had penetrated through the defenses

of the Siegfried Line just to the north of the wooded quagmire. On November

16th, using nighttime maneuvers, they attacked and under the cover of

darkness, secured the village of Stolberg, continuing the drive against a

determined German resistance to the village of Eschweiler. During this

drive, on November 18th, Paul Rheinheimer was wounded, and with any luck, it

would be his million dollar wound that would take him out of action and

danger for good. His healing powers, as exemplified by his recuperation from

the car accident four year earlier, were too good, however, for after lying

in a military hospital in England for six weeks, he recovered from his wound

and returned to his unit along the front. Though he had earned the Purple

Heart, it was small consolation for the danger he returned to along the

warfront.

Towards the end of the conflict, the Allied army relentlessly pushed the

retreating Germans eastward, back to the Rhine River. In their pursuit,

little hope was held by the American commanders that bridges over this river

would be left standing by the retreating Germans, hindering the American

army's final drive. To their surprise, however, the railroad bridge at

Remagen, left standing to allow the last vestiges of German army units to

escape the advancing Americans, was still intact, and was quickly pounced

upon by the Americans. For two weeks during the middle of March, 1945, the

battle raged for the control of this bridge and the establishment of an

American army bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Rhine. Pontoon bridges

were placed across the Rhine, down river from Remagen, to aid in the

struggle and to expand the bridgehead. The 104th Division crossed the

pontoon bridge at Honneff on the 21st of March to join in the expansion of

the bridgehead, already ten miles deep. On the 24th, a moonlight attack by

units of the 104th near the village of Rottbitze, was met with heavy mortar

fire and sweeping machine gun cross-fire, the Timberwolves taking heavy

casualties....

Henry Rheinheimer was now eighty-four years of age; eighty-four years of a

long, eventful and memorable life that was now fading from his memory.

Recognizing people was difficult, remembering moment to moment impossible,

becoming lost with confusion and anxiety as his family and friends were

turning into strangers. This long trust-worthy soul could no longer be

trusted to be left alone. No longer could he venture out on his own, with

fear of not knowing if, how or when he would return. He was also a danger to

himself, recently being struck by a car on a Youngsville street. When Alice

could no longer take care of him, she committed her husband to the Sullivan

County Home at Thompsonville during the spring of 1943. There, he was to be

constantly watched for he was known to wander. Shortly after the noon meal

on a hot August afternoon, 1943, Henry wandered off into the neighboring

woods, his departure noticed by fellow residents but not by the staff. When

finally discovered that he was missing, a "diligent" and "extensive" search

was conducted by the County Home's staff, who were unable to find his

whereabouts.

In the spring of 1945, Alice Rheinheimer was now alone; her husband, two

years after his disappearance from the County Home, was still missing and

their three sons were now serving overseas with the armed forces. Hopes were

now high on the home-front that the war would soon conclude, ending its

deadly rampage, as news of the Allied successes against the German was

reported back home; it was only a matter of time before the enemy

surrendered. For Alice, hopes of all her sons soon returning home were

dashed when on April 27th she received the telegram from the War Department

informing her that her son, PFC Paul E. Rheinheimer, had been killed in

action on the 24th of March. For the soldiers along the warfront fighting

against the remaining German resistance, they also knew that the war would

soon be over. The goal now, for each man, was to survive this final month of

battle and make it back home. For Paul, he was not so lucky. Paul

Rheinheimer did return and was given full military honors during the burial

ceremonies conducted at the Veteran's Cemetery.

Deer hunting season is like a religion to some folks here in Sullivan

County. During a few weeks of each November, a small army of hunters take to

the fields and forests, often traipsing over ground that normally would

receive little human traffic through the course of the rest of the year. On

opening day, November 19th, 1945, a party of hunters were in a patch of

woods, about a half mile from the County Home, when at noon George Hindley,

one of that party, came upon the remains of a human skeleton, strewn about a

fifteen foot section of the forest's floor. State troopers and deputies from

the sheriff's department investigated the scene, and judging by the growth

of vegetation, indicated that the skeleton had probably been there for two

years. Further identification was made when the shoes found amongst the

bones where known to have come from the County Home. The final conclusion

was that Henry Rheinheimers wandering from the County Home led him to this

patch of woods, not that far away, where he aimlessly roamed about until

overcome from exhaustion. "Picnic Heinie's" whereabouts were finally

discovered, but as luck would have it, he has disappeared again; his final

resting place is unknown. - Fred