![]()

Unfavorable weather conditions over enemy targets within Germany had grounded Allied bombing mission in late March of 1944, so when the skies cleared over France on the 27th, the command of the Eighth Army Air Force dispatched the fleet of bombers, including the 784th Bomber Squadron of the 466th Bomber Group, against airfields in France used by German fighter planes. Liberator pilot Harry Sturdevant's bomber, nicknamed the Stardust, was part of this group. Though weather conditions on that morning were to improve later in the day at the Stardust's airbase, Attlebridge, England, morning conditions shrouded the airbase with low cloud cover and limited visibility when the big bomber lifted off the runway. Once in the air, the Stardust came upon the other bomber squadrons involved in the mission and as the big planes were forming into formation, twelve miles from base, the Stardust collided with another B-24. Heavily damaged, both planes went down. The Stardust's pilot attempted to land the crippled aircraft in a farmer's field but fell short and crashed into a nearby marsh. As farm workers were coming for the crew's rescue, the plane exploded. All ten crew members of the Stardust perished in the inferno. For Harry Sturdevant, though, it was his lucky day. Since he and a fellow crewmate were sick with bad colds, the whole crew was grounded that morning for the French airfield mission. The ill-fated substitute crew on the Stardust that morning was piloted by Robert Mogford. Harry and his crew would continue to fly bombing missions.

Like so many other

Americans who were spellbound by the flight across the Atlantic of Charles

Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis in 1927, Harry Sturdevant and his family began

an interest in flying. Harry's father, Harry Sturdevant Sr., an engine mechanic,

was the proprietor of the Sturdevant Garage. The business started when Harry

Sr., along with his brother Elmer, opened a small shop on lower Main Street in

1913, next to the Dawson iron foundry. When the foundry business went bankrupt,

Harry moved his garage into the more spacious quarters of the old foundry

building. Soon after the move into the new location, Harry married Lydia Conklin

and on August 17, 1916, a son was born to the couple.

Like so many other

Americans who were spellbound by the flight across the Atlantic of Charles

Lindbergh's Spirit of St. Louis in 1927, Harry Sturdevant and his family began

an interest in flying. Harry's father, Harry Sturdevant Sr., an engine mechanic,

was the proprietor of the Sturdevant Garage. The business started when Harry

Sr., along with his brother Elmer, opened a small shop on lower Main Street in

1913, next to the Dawson iron foundry. When the foundry business went bankrupt,

Harry moved his garage into the more spacious quarters of the old foundry

building. Soon after the move into the new location, Harry married Lydia Conklin

and on August 17, 1916, a son was born to the couple.

The business expanded with the addition of an automobile dealership, vehicles

assembled and customized at the plant. Besides automobiles, Harry Sr., with his

son, assembled engines on other apparatus, such as portable sawmills and

ice-cutting saws. One notable project was a motorized iceboat that the

Sturdevant's skated over the frozen Willowemoc Creek and Shandelee Lake.

Airplanes, and flying, were now to be another horizon for both father and son to

explore.

Building his own airplane, Harry Sr. searched for a place where he could land

and take off from. Just south of the Manor was the ideal place, the cabbage

fields of the Blake Barker farm, where in the past, aviators used the field,

avoiding the crops, as a landing strip. Harry Sr. leased the field from Barker

in 1932, had it surveyed, and with Merritt Tompkins, proprietor of the new

garage at Deckertown and who also helped in assembling the Sturdevant plane,

leveled the cabbage patch into a suitable landing strip. The Barker farm became

noted onto aviators' flight maps, with aviators using the new landing field and

with some pilots performing exhibition shows, arousing the interest of the

residents of Livingston Manor. Harry Sr. became a flight instructor, teaching

many of the local residents the basics of flying, his son becoming his prize

student.

Harry Gordon,

from Long Island, leased the Barker landing strip in 1938 and established the

old cabbage patch airfield into the Livingston Manor Airport. It was now listed

in the Airport Directory as an auxiliary and emergency field, the sod runway

being over 1,500 feet in length. A hanger that would house up to five planes was

erected and runway guides and a windsock installed on the field. With fellow

Long Island pilot Alfred Brazog as teacher, a flight training school was

started. Brazog, who had previously operated the Jamaica Sea Airport, on Long

Island, and was a noted skywriter, also began an air-mail service out of the

Manor and maintained a cabin aircraft at the airport for passenger flights.

Harry Gordon,

from Long Island, leased the Barker landing strip in 1938 and established the

old cabbage patch airfield into the Livingston Manor Airport. It was now listed

in the Airport Directory as an auxiliary and emergency field, the sod runway

being over 1,500 feet in length. A hanger that would house up to five planes was

erected and runway guides and a windsock installed on the field. With fellow

Long Island pilot Alfred Brazog as teacher, a flight training school was

started. Brazog, who had previously operated the Jamaica Sea Airport, on Long

Island, and was a noted skywriter, also began an air-mail service out of the

Manor and maintained a cabin aircraft at the airport for passenger flights.

Harry Sturdevant Jr. graduated from Livingston Manor High School in 1936. He

worked alongside his father at Sturdevant's Garage, joining his father in the

operation of the business in 1940. After being taught by his father the basics

on how to pilot a plane, Harry Jr. continued taking flight lessons with Brazog,

a more advanced training course, and in June of 1939, passed the final test at

Roosevelt Field, receiving his pilot's license. Harry Jr. now planned of

becoming a flight instructor himself.

View of the Livingston Manor Airport, before the

fire, from the end of the abandoned runway

With the drums of war beating across the Atlantic, the Barker airfield took on

new importance with the national government. Being located near Route 17,

considered at the time as a military highway, routes that were vital for

transporting troops, and close to the O&W Railroad, the Livingston Manor Airport

took on new importance in the war effort. The report issued by the Civil

Aeronautics Authority in 1940 also felt that since the Manor airport was ideally

nestled in the mountains, it could easily be camouflaged. The airport facility

became part of the national defense program and a National Defense School was

established at the Manor school, with classes beginning in February of 1941.

With Harry Sturdevant Sr. designated as the instructor, many high school

students were to receive preliminary flight instruction. Harry Sturdevant's

vision of turning the Barker cabbage patch into an important transportation link

for the local community would now, with the beginning of the world's

hostilities, begin to have a large impact on many of the local families,

including his own.

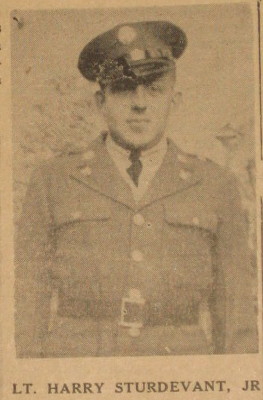

Harry Sturdevant Jr. enlisted into the Army on March 5th, 1942. He was initially

attached with the Coast Artillery but after four months, because of his previous

flight experience, he was transferred to the Army Air Corps and began the

rigorous training needed to fly the big four-engined planes, the B-17 and B-24

heavy bombers. Harry completed his basic flight training in April of 1943 and

was issued the Silver Wings award, which he sent back home to his proud father.

Advanced Flying School was next, where he trained to fly the heavy bombers. On

July 28th, upon graduating from the school, Harry received his "Wings" and was

commissioned lieutenant. Finally in October, for the first time in seventeen

months since joining the Army Air Corps, Harry came home on furlough, looking

smart in his uniform, his father bursting with pride for his son's

accomplishments.

Lieutenant Sturdevant was attached to the 466th Bomber Group, which arrived at

the Attlebridge airbase, in England, on the first of March, 1944, a part of the

Eighth Army Air Force, but it wasn't until the sixth of April when his parents

received word of his safe arrival overseas. Little did they realize that within

two days of receiving the good news of their son's safety, uncertainty would

forever shadow their remaining years.

After the loss of his plane the previous week, Sturdevant's crew was assigned

onto another B-24 Liberator, and in spite of being considered bad luck, the crew

renamed the aircraft the Stardust. On April 8th, Eighth Army Air Force command

sent three bomber forces, one of the largest mission to date, against military

targets in heavily defended northern Germany. The 784th Bomber Squadron of the

466th Bomber Group, Lieutenant Sturdevant's unit, was part of the first force

which was ordered to attack German airfields and aircraft factories in the

Brunswick-Hanover sector. To avoid congestion, the large fleet of 639 heavy

bombers, along with the fighter escort, left the British coast at separate

points, all converging on the Dutch coast. Since the Brunswick targets were the

most distant, the first force was the first to make landfall across the Zuider

See and were to receive the heaviest opposition. After the Brunswick force had

flown north of the target area, it turned to the southwest to begin its bombing

run, encountering heavy ground flak and engaged by as many as 150 German

fighters. After dropping their payloads throughout the ensuing air battle, the

damaged bombers that became stragglers were pounced upon by the aggressive

German fighters, these bombers' fate unknown to the remaining force. The initial

military report of the Brunswick mission after the return of the fleet were that

a total of thirty heavy bombers were observed to have been shot down, the

majority from action against enemy fighters. Three other bombers, including the

Stardust, did not return and they, along with their crews, were listed as

unaccounted for.

On Sunday, April 23rd, 1944, Harry and Lydia Sturdevant received the letter from

the Adjutant General's office, informing them that their son, Lieutenant Harry

Sturdevant Jr., has been missing since April 8th. With the lack of any other

information coming from the War Department concerning the fate of the Stardust

and its crew, the parents' hopes were high that Harry landed the stricken bomber

somewhere, perhaps as rumored in Switzerland, or bailed out and was either a

German prisoner of war or perhaps sheltered by the French underground. In this

particular case, no news was considered good news to Harry and Lydia Sturdevant.

Their hopes were further lifted when in the middle of September, a message was

sent to the Sturdevants from the mother of Sergeant William McMyne, the

ball-turret gunner of the Stardust. Mrs. McMyne received a letter from William,

through the American Red Cross, which stated that he was a patient in a German

hospital and expected to be sent to a German prison camp. It now seemed quite

possible that Harry, also, may have escaped the crippled plane.

For over a year the parents never received any official word concerning the fate

of their son. After the war in Europe was finally over the following spring, and

after a year of anxiety, the father received a letter from the bombardier of the

Stardust, Lieutenant Thomas Twisdale, who confirmed the parent's worst fears.

The Stardust, as written by Twisdale to the grief-stricken parents, received

heavy flak damage during the Brunswick raid. As Sturdevant struggled behind the

controls to keep the plane aloft, three members of the crew, including Twisdale

and McMyne, were able to bail out. An enemy fighter then struck at the bomber,

and as Twisdale slowly parachuted down after his escape, he saw Sturdevant

frantically working the pilot controls as the plane plunged to earth into a

fiery crash. While as a prisoner of war, Twisdale attempted to relay the

information concerning the fate of the remaining seven crew members on board

through letters to his wife, but Army censors repeatedly cut any information

regarding the tragic event.

For over a year the parents never received any official word concerning the fate

of their son. After the war in Europe was finally over the following spring, and

after a year of anxiety, the father received a letter from the bombardier of the

Stardust, Lieutenant Thomas Twisdale, who confirmed the parent's worst fears.

The Stardust, as written by Twisdale to the grief-stricken parents, received

heavy flak damage during the Brunswick raid. As Sturdevant struggled behind the

controls to keep the plane aloft, three members of the crew, including Twisdale

and McMyne, were able to bail out. An enemy fighter then struck at the bomber,

and as Twisdale slowly parachuted down after his escape, he saw Sturdevant

frantically working the pilot controls as the plane plunged to earth into a

fiery crash. While as a prisoner of war, Twisdale attempted to relay the

information concerning the fate of the remaining seven crew members on board

through letters to his wife, but Army censors repeatedly cut any information

regarding the tragic event.

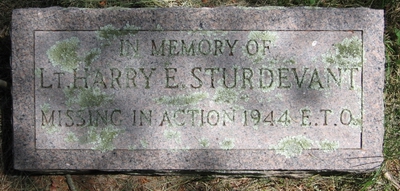

Supposedly, the site of the Stardust's impact was later discovered, but little

of the crew's remains could be found and identified. Personal effects were sent

home and a granite memorial stone placed in memory of Lieutenant Sturdevant was

placed just behind the iron railing of the Lew Beach Cemetery. Harry Sturdevant

Sr. was never to be the same since. He died of heart disease ten years later,

but those who knew him suspect it was more likely from a broken heart.

The Livingston Manor Airport has lain abandoned for many years now, the main

building just recently destroyed by a spectacular fire. The cabbage patch

landing strip, though, is still used, but not by any Cessna or Piper Cub, but by

model airplane enthusiasts. On any given Saturday morning, model airplanes can

be seen circling the field, being remotely controlled by a son being trained to

fly the small aircraft by his father; not unlike a father and son's dream

seventy years before.

Fred