Along The Willowemoc

<click pictures for full-size>

Willowemoc Acid Factory -

2/20/2010

Another geologic feature in the valley of the upper

Willowemoc, this one man-made, looms as witness to a portion of the valley's

history. Standing high above the surrounding encroachment of trees and

brushy undergrowth, a stack of brick and mortar form the crumbling chimney

that rises eighty feet above the ruined remains that for thirty-five years

during the turn of the previous century, housed the valley's principle

industry and the economic lifeblood for its resident; the acid factory of

Stoddard Hammond. Today, exactly one hundred years following the death of

Mr. Hammond, the chimney is now a monument to him and to those families from

that era that still remain in the valley, their ancestral foundations as

deeply rooted in the Willowemoc valley's soils as the chimney's cement

foundation that hold the old factory's smokestack upright, straight and

true.

It was during the early winter of 1891, before any work on the factory

building itself had started, when an army of men and teams of horses set out

into the forests that surround the Willowemoc, cutting down the timber and

hauling it to the grounds where the factory was to be erected. For four

years, ever since the purchase of over four thousand acres of timberland by

Stoddard Hammond, there had been much talk throughout the valley about the

rumor of the wood-chemical industry moving up into the valley and the

building of an acid factory at Willowemoc, and now with the four-foot-cut

lumber being stacked at the site, the rumors were now believed to be

apparently true....

The building material needed for the construction of Stoddard Hammond's factory was brought in by the railroad and unloaded at the Parksville and Livingston Manor depots, which then needed to be carted over the primitive roads leading to Willowemoc. Among the items were sheet metal used for sheathing the building, eight retorts used in the wood burning process, and fifteen carloads of bricks, some of which were to be used for lining the ovens and others for the erection of the eighty-foot smokestack. Throughout the spring of 1891, carpenters and laborers worked non-stop at the the factory site. By June, the main building was enclosed, sheathed with iron and the masonry work almost completed; a structure that was two hundred and seventy-five feet in length and thirty feet wide. The main, and final obstacle keeping the factory from beginning operation was the setting up of the plant's main heating boiler...

Early in July, the boiler that would serve as the heating plant for

Hammond's acid factory arrived on the rail cars at Livingston Manor. The

behemoth's weight of over eight tons strained the railroad company's bridges

and trestles along its route as they shook and trembled under the load, as

well as straining the nerves of the railroad men who must have also shook

and trembled with fear as their train passed over each river crossing. On

its arrival, the boiler was unloaded onto trucks, sets of wheels that were

similarly used by the railroad cars, and hauled over the countryside to its

destination at Willowemoc with as many as nine teams of horses needed for

the move.

Normally, the journey from Livingston Manor to Willowemoc would require some

two hours of a face-paced walk but this was not the case for the men, the

teams and the burden that they dragged behind them; it took four days to

make the nine-mile journey. Along the way, bridge crossings over the

numerous creeks needed to be braced with timbers for added support to allow

safe passage of the boiler, but even with these precautions being made, many

bridges gave way under the overbearing weight, adding to the miseries of

both men and beasts. By the middle of July, the boiler had finally made it

to the factory site and was placed in position. With thirteen hundred cords

of four-foot wood already stockpiled on the factory grounds from the past

winter's work, the boiler was now ready to be fired up and the plant's

operation set to begin on Hammond's self-imposed deadline of August first.

The acid factory of Stoddard Hammond was in a somewhat

unusual location. Situated in the isolated upper portion of the Willowemoc

valley, it was not close to the area's transportation lifeline of the

Ontario and Western Railroad, as were the other chemical plants of

Hammond's competitors, and the crudely constructed rural roads to and from

Willowemoc were often unable to handle the increase traffic volume. To help

insure a reliable route to haul the plant's products, a macadamized road was

built over the hill connecting the now busy community of Willowemoc to

Parksville, shortening the distance to the railroad's cars by some three and

a half miles.

Willowemoc flourished as the plant employed as many as twenty-five men who

worked on the factory's grounds. In addition, contracts were let out to area

businessmen and individual farmers to supply the plant with the necessary

four-foot cordwood. During the peak years of factory's operation, as much as

ten thousand cords of wood were brought into the yard. All this work, both

at the plant and in the forests, provided employment for the growing number

of area residents as Willowemoc began taking on the appearance of a thriving

boom town. Structures were built to house the workers and their families,

local businesses thrived and a church was erected. The sound of the

factory's steam whistle, calling the men to and from work morning and night,

echoed throughout the valley with the tune of prosperity.

During the operation of the family's tannery at Debruce,

Stoddard Hammond resided along-side the employees who worked at his plant,

and with being an ardent hunter and fisherman, enjoyed the wilderness

setting of rural life that the upper Willowemoc valley offered. His third

marriage however was to a Binghamton socialite who enjoyed the cultivation

offered by refined civilization more so than that of a plowed field. The

couple moved to Binghamton where she participated in many socials circles

and joined many women's clubs. As for Stoddard, he filled important

positions in Binghamton's political and financial circles, attending his

Willowemoc business affairs from afar, with only the occasional visit back

to the forests, streams and ponds he had always enjoyed but had now come to

miss. Early in 1909, Stoddard gave up living in Binghamton and moved his

possessions to one of the cottages at Willowemoc near the factory and was

once again residing amidst the families that depended on him for employment

and well-being, and he on them for the successful operation of his factory.

Midway into the cold winter of 1910, the daughter of Stoddard Hammond had become seriously ill, prompting a visit by him to her home in Boston, accompanied by his wife and other daughter. They returned after the visit by the railroad on February 12th, arriving at Livingston Manor in the midst of a tremendous snow-storm. The stage-coach from the station was able to make its way through the drifted road to Willowemoc, arriving in the early evening's winter darkness, but the driver was unable to drive the coach down to the Hammond cottage due to the deep snow. Stoddard insisted on walking the final one hundred yards through the blowing snow and deep drifts. Once to the cottage, his wife and daughter attended to the wood stove as the exhausted Stoddard rested in his chair near the stove. With the fire set and the stove beginning to warm the room, the ladies became engaged in a discussion over the facts concerning the family's recent journey, when they were startled to find that Stoddard had slid off the chair and onto the floor, where he soon expired.

Stoddard Hammond, the last member of the family whose business endeavors

begun by his father changed the landscape of the Willowemoc valley along

with the surrounding hillsides within a period of sixty years, was dead.

Operation of the acid factory continued on, now under the proprietorship of

"Ren" Roosa, but with the fiery destruction of his just recently constructed

hotel at Willowemoc, soon leased the plant to the firm of G H Treyz in 1915.

Ten years later, during a similar wintry snowstorm that was partially

responsible for the death of its original owner, the snow-filled sky that

hung over the upper valley of the Willowemoc cast a red glow coming from the

flames that completely consumed the Treyz acid factory. Little could be done

to save the buildings, as fireman coming from Livingston Manor encountered

roads so covered with drifting snow that when they finally arrived, all that

remained standing was the smokestack.

Now, eighty-five years later, the forests along the valley of the Willowemoc

are again replenished with both the hardwood and hemlocks as the onslaught

of wood-choppers that supplied the Hammond enterprises for over a half a

century have ceased denuding the hillsides. Left standing as witness to the

history of this era and a reminder of those who lived within the shadows of

the smoke it generated, is the slowly decaying chimney of the Hammond acid

factory, still towering above the invasion of hardwood trees that the

smokestack had once earlier consumed

Headwaters of the Willowemoc by Fluggertown Road

- fred

********************************

Willowemoc Headwaters

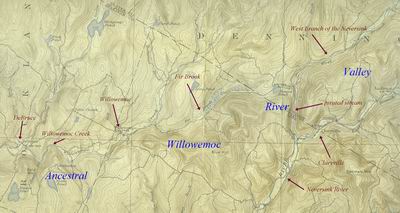

The course of the Willowemoc Creek, as it flows above Livingston Manor,

follows a broad, generally east-to-west orientated valley, its current

existing physical characteristics being the result of past eons of glacial

activity. The broadness of the valley suggest that in the past, valley

glaciers flowed through the pre-existing river valley, scouring the bedrock

along the valley walls to create its present width. The most recent glacial

activity, the continental glacier which had a northeast-to-southwest flow,

filled in much of the valley with glacial debris, ice transported soils and

rocks, that influenced the location of the stream, which runs its course for

the most part along the base of the valley's southern wall.

The east-west trending section of the Willowemoc valley begins at the

community of Willowemoc and follows a westward course to Livingston Manor,

where it then bends sharply northwestward to its eventual confluence with

the Beaverkill River. This portion of the valley, however, is only one-half

of the original valley's length for at one time the valley that now carries

the flow of the West Branch of the Neversink River was once the headwaters

of the Willowemoc. Through a process geologically known as stream piracy, a

tributary stream that fed into a neighboring, parallel valley, eroded

head-ward until it breached the ancestral Willowemoc Creek valley wall,

diverting the upper portion of the Willowemoc's flow, creating a deep notch

in the bedrock until it reached the new recipient stream, today the

Neversink River at the community of Claryville. The resulting landscape,

besides the deep notch, is the diminutive tributary stream, Fir Brook that

now flows along this portion of the ancestral Willowemoc valley. Fred

******************

The most recent visit by glaciers into the Willowemoc Creek's valley, perhaps ten thousand years ago, is responsible for much of the valley's current landscape. As the valley glacier drove down the Neversink River's west branch valley, the ancestral valley of the upper Willowemoc, a lobe of ice spilled over the valley wall, following roughly the same course of the original valley, near what is now Round Pond. This ice flow continued for about a mile where it then stalled, the edge of the glacier melting as fast as it was being fed more ice from the glacier's flow. Debris in the form of rocks and boulders piled up as the glacier continued to transport the material to the edge of the ice.

Ice, which earlier had entombed the whole Willowemoc valley with the continental glacier ice, had already melted and disappeared from the valley that the Neversink glacier invaded, the valley now being filled with water, the result of a small glacial lake formed when glacial debris dammed the valley downstream. Water from the melting Neversink glacier now fed into this lake, carrying the finer debris of gravel, sand and silt off of the glacier into the valley and being deposited onto the lake's bottom, further filling-up the valley with this fine material. Finally, the water from this glacial-runoff swollen lake breached the dam below, leaving behind a section of the ancestral valley filled with silt and sand, today's Fir Brook valley.

Currently, Fir Brook slowly

meanders through this valley, its channel cut into the sand and silt

deposited thousands of years ago by the glacial runoff. Trees along its

shores, its roots precariously anchored only by the loose sand and silt,

easily topple into the stream. Groves of fir and hemlock that thrive in

the deep sandy soils fill the valley, surrounded by native hardwoods that

were once so much sought after by previous generations of area lumbermen.

The valley, its characteristics somewhat unusual here in the midst of the

Catskills, has an Adirondack aura to it. Wildlife, of course, abound;

particularly noted are the various species of flycatchers that nest here

and spring peepers, who in the early spring announce the end of

winter with a full-throated chorus that fills the valley with the

high-pitched uproar, heralding the coming warm weather. - Fred

************************

Willowemoc Kiosk

The history of one of the region's oldest communities is preserved and now

shared with us all by the erection of an informational kiosk at the hamlet

of Willowemoc. Located on recently acquired state land, the kiosk is at the

newly developed Department of Environmental Conservation fishing access

site, and coupled with a DEC regional informational board, overlooks the

Willowemoc Creek.

It is the creation by the folks from the community, the structure built by

the craftsmanship of cabinet-maker David Forshay, the artwork and layout by

Caroline Bivins, history provided by local residents, led by Robert Decker,

and the site artfully landscaped and the kiosk's completion aided by the

help of the community's residents.

Word of this project spread around Livingston Manor this spring as meetings

were set up with the Town of Neversink historian, whose township most of

Willowemoc area lies in, in pursuit of historical information, with Manor

residents who have ancestral ties to Willowemoc invited to attend. The

resulting story, as told on the kiosk, follows the development of the

Willowemoc area from Matt Decker to the Treyz acid factory to the building

of the New York City water tunnel, including many of the people who helped

shaped the community over the years.

The kiosk can be found on the main highway, just after crossing the bridge

over the Willowemoc. You can't miss it....and by all means, don't miss it.

- Fred

********************************